Hierophanies were important spiritual experiences that linked the Maya with their ancestors, gods, and surrounding sacred landscape. “The royal palace complex also provides a dramatic seasonal assertion of the earth’s power, expressed with clamoring fervor. Just below the palace platform lies the Cueva de Murcielagos, which serves as the outlet for an entire drainage system. After heavy rains, water discharges from this cave (figure 6.3) with such force that the roar [roar of the cosmic Serpent, the embodiment of water, acting from the centerplace as the axis mundi] can be heard more than a half kilometer away. This was a predictably repeating hierophany, a manifestation of the sacred, surely on a par aurally with .the public visual hierophany of the dying sun’s winter solstice descent into Pacal’s tomb at Palenque (Schele 1977), or the effect of light and shadow transforming staircase to serpent on Chichen Itza’s Castillo at equinox sunset. …The sound hierophany at Dos Pilas is a transformative call, a metronome of the seasons. It specifically signals the onset of the rainy season, and thereby the advance of the crop cycle. Because the king was responsible for crop productivity and quality, identifying his palace with this dramatic water source seems hardly coincidental and, in fact, a conscious political strategy, re-expressed every year. The landscape itself thus loudly proclaimed the king’s control over water [king is the embodiment of the axis mundi], and presumably over rain-making and fertility. …Interestingly, and not coincidentally, that is exactly the claim made in the first millennium BC by a non-Maya king on Chalcatzingo’s “El Rey” panel, where wind issues from the mouth of a cave portal, on whose wall a ruler is shown seated in a cave mouth, and next to which ancient artificial channeling concentrates the mountain’s rainwater run-off into a seasonal torrent” (Brady, Ashmore, 1999:129-130).

In short, this ideational landscape, the epitome of the ancestral Snake-Mountain/cave-Cloud/lightning narrative of Twisted Gourd symbolism that was the cosmology and visual program of social elites, materialized a pan-Amerindian cosmology and ideology of leadership and extended it into communities. It is interesting to note that the divine kings, as embodiments of the axis mundi, acquired great loyalty and tribute by taking credit for natural processes so long as those processes benefited the community. The divine kings were also warrior kings, and lack of success in repelling an attack or attacking one’s neighbor very likely had the same deleterious effect on the confidence of a community that a drought would have had.

The meaning of “tinkuy” as a ritual catalytic encounter is a type of hierophany mediated through the transformational nature of water that included decapitation, sexual rites, ritual battle, shamanic flight, and light-water rites in a ritual landscape as described below invites the suggestion of an overarching structural and functional idea that points back to the premise of the water cycle itself, which at minimum included the perceived movement of the Milky Way (cosmic Serpent, amaru) and the ecliptic path of the sun. In the cosmic Serpent, the amaru, which was coidentified with the Milky Way as a river of life, there was a unitive concept that was sentient space. Out of this sentient space, which Maya and Pueblo myths described as a foggy, primordial state with an inherent potential for lightning, the cosmic Serpent materialized as the personified Sun, which gave rise to dualism and the fire : water paradigm that instantiated life. From the Moche to the Maya to the Pueblo divinized ancestors, this fire/light : water/space dualism would define the nature of the Makers, the sky-earth connection (axis mundi), the first divine humans from whom the Snake sun kings would descend, and the cosmic nature of legitimate political and religious authority.

“The ancient Maya [and the Andeans] exhibited their scientific and spiritual understanding of the cosmic realms through astronomical hierophanies” (Mendez et. al, 2012). So did the ancestral Puebloans as attested by the trademark of the Bonitian dynasty at Pueblo Bonito, the “Chaco signature,” which was derived from interconnected Twisted Gourd symbols and as such was a holy tinkuy, a hierophany, a manifestation of the sacred that was associated with the nature of rulers and the catalytic rituals they performed in the sacred precinct of the kiva, which symbolically was the cosmic center in the heart of the ancestral Mountain/cave. Twisted Gourd symbols were water connectors, meaning the ancestral Snake-Mountain/cave-Cloud/lightning narrative associated with the Twisted Gourd symbol defined the nature of the connection, the tinkuy, between the liminal realm of the cosmic Serpent and the physical reality of water on the terrestrial plane, which was materialized ritually as smoke clouds and medicine water, through the “misty” centerplace of the Mountain/cave, which as the kiva was the interface between the two realms.

13th century Tusayan serial Twisted Gourds (above) with the interlocked and enfolded double stepped triangle derived from it, the “Chaco signature” below it. The top symbol was associated with central authority; the bottom symbol was the regional tinkuy signature that materialized the igneous : aquatic paradigm (see main report). Both referred to the Snake-Mountain/cave-Cloud indexical metaphor to which the Twisted Gourd symbol referred, which was a shared community of thought. See ML015591 for the Peruvian 800-200 BCE antecedent to the Chaco signature.

Urton (Fig. 2) showed that the ecliptic wasn’t necessary to form the celestial Kan cross as the Maya have it; the movement of the Milky Way alone was enough to account for it. This is represented by the association in the image to left of the Milky Way checkerboard and the Rotator that can spin in either a sinestral or anti-sunwise direction (see Rotator). The Rotators, then, were a visual clue to the location and movement of the Milky Way and, hence, the wet or dry season.

That said, the encounter of the ecliptic with the Milky Way at the solstices had to be significant to the ancient water wizards; in the southern hemisphere it signified the change from wet to dry season at the June solstice, and vice versa at the December solstice. According to their art the Dragon nature of the Milky Way came to the foreground at these times, but the Dragon had prominent lunar associations, not solar. Therefore, to the Peruvians who invented the Twisted Gourd symbol and developed the light-water encounter of the tinkuy ritual, the fact that the Milky Way and solar ecliptic crossed paths at the solstices may not have been the light-water tinkuy that made the “rainbow” path of the ancestors that was so important to sustaining life.

This report argues that the all-important tinkuy was conceived of in another way that is consistent with triadic cosmology on the two solstices when the Milky Way was the night-time Zenith, and twice a year midway between those events when the noon-time sun was the daytime Zenith. Therefore, in at minimum four annual events the crucial celestial N-S axis made the light-water tinkuy by connecting the Milky Way with the sun in alternate Zenith and Nadir positions vis a vis the celestial sphere and underworld. For locations too far north or south of the equator to experience the sun directly overhead at noon, the zenith position of the sun at the equator could easily be calculated from any location using the solar zenith angle and simple geometry. For the accomplished priest-astronomers that the water wizards were, this would have been grade-school mathematics. Likewise, given how interested both the Peruvians and Chacoans were in lunar standstills, other light-water tinkuys that connected the Above and Below realms of the triadic cosmos may conceivably have related to the position and phase of the moon; the moon at its zenith in the night sky may have had some relation to the position of the Milky Way and the sun.

Probably one of the better documented tinkuys was discovered at Chavin de Huantar, where an underground aquaduct conceived of as the Milky Way as it flowed through the underworld was accessed by stairs that led into a cruciform chamber inside a major temple c. 850-700 BCE. At the point where the arms of the cross intersected was placed the famous serpent-jaguar Lanzon monument, which was struck by light once a year as the sun rose on the June solstice, or winter in the southern hemisphere (Kelley and Milone, 2011:439).

Rick, who researched the underground canals at Chavin de Huantar, defined tinkuy in that context as “ritual encounter between people and water” (Rick, 2017:41). The underground canal system served as a tinkuy by integrating performative ritual with a sensory, Disneyesque experience of the triadic world and the water cycle (Rick, 2017:44-45). That sense of encounter with water–with technology, priests, and a sophisticated visual program of an ecocosmovision on one side, and pilgrims bearing offerings of Strombus and Spondylus shells and food alongside craftspeople bearing their best weavings and gold ornaments on the other– is also a snapshot of the basis of their hierarchical social structure.

Another impressive tinkuy was found at Moro de Eten in the Lambayeque Valley in northern Peru c. 400-200 BCE. There, an ancient road passed by a pyramid and led to a cliff overlooking the sea. During most of the year, “the road seems purposeless, but at the December solstice the light of the setting sun, reflecting on the water, makes a brilliant golden extension of the road into the Pacific to the western horizon” (Kelley and Milone, 2011:441).

However it was conceived, a catalytic ritual encounter as a simultaneous celestial and terrestrial tinkuy of moving parts recalls the spinning and whirling imagery of the rotary symbol shown above in the checkerboard pattern that represented the Milky Way. The Rotator was associated with sexual relations, battle, and shamanic flight; the tumbling motion of the sacrifice by mountain descent; and the tumbling of water as a river was diverted into an irrigation canal.

It was at the points of contact during the solstices and equinoxes where the people’s water requirements intersected with Milky Way positions, where shamans could mediate between nature and culture by creating the catalytic light-water tinkuy. Ritually, the place of encounter where all interested parties could meet and human interests could be represented was the catalytic zone between the cloud and the mountain, hence the significance of the serpent-mountain-cloud symbology of the Twisted Gourd itself and the terrestrial power of the serpent-jaguar mountain deity impersonators (priest-astronomers), who were represented by those symbols. The mountain-cave was the nexus of all the sacred directions but crucially the celestial N-S axis.

Logically, due to the importance of celestial processes to terrestrial life and well-being, it is hard to conceive of anything more appropriate than the Milky Way as the necessary ecological basis for the ritual efficacy of the original idea of the tinkuy, as symbolized by the Twisted Gourd and its derivative form, the enfolded stepped triangles that unfold into the bicephalic serpent bar. The idea of creating a terrestrial monument–canal, pyramid, etc– that mirrored a celestial process and mapped celestial sacred directions onto a mirrored terrestrial landscape where the cave-shaman served as the bridge between the celestial and terrestrial constructs points to the geometric symbols that represented these constructs. The (serpent-feline-mountain/cave plus cloud) Twisted Gourd tinkuy signified the centerpoint meeting place, which was connected with the cosmos through the water cycle. The two-color cross with eight partitions signified the cardinal and intercardinal directions with a centerpoint. The celestial N-S axis connected the celestial and terrestrial centerpoints with the underworld at the solstices and equinoxes. The several forms of the Rotator, which included the swastika, was a directional and calendrical pointer to the rotating movement of the Milky Way serpent and the catalytic tinkuy event that was taking place.

A great deal of research has shown that the arrangement of Great Houses in Chaco Canyon have astronomical alignments, although no work has been done on how the location and position of the Milky Way associated with those alignments. Penasco Blanco was identified as a possible sun station to observe the winter solstice. It was associated with a road and had what was interpreted to be a “clear sun symbol” painted on a nearby canyon wall (Mathien, 2005:220). The symbol was concentric circles with a dot in the center which, as was seen throughout Peru and will be illustrated again for Monte Alban and Chichen Itza, for sites with significant Twisted Gourd imagery which includes Chaco Canyon and the San Juan Basin the concentric rings symbol refers to a triadic world structure (see Concentric Rings) and the serpent-mountain motif. The outer ring is the sky-water band of the water serpent, the innermost centerpoint refers to an archetypal mountain, and together the image reduces to blood-water, which is Milky Way ideology. In other words, what is interpreted as a sun symbol is the cosmic bicephalic serpent. When the serpent-mountain centerpoint is struck by the sun, a light-water tinkuy occurs.

While it may be impossible to reconstruct ancient water rituals outside of the legacy of Moche ceremonial art, these clues of ritual simultaneous motion geared to celestial tinkuys involving the Milky Way and sun provide a context of interpretation that may prove to be useful when it comes to identifying water tinkuys that were built into a ritual landscape so as to mirror a celestial event and thereby bring the material and spiritual orders into contact.

After the Moche phases the Twisted Gourd ideology persisted in political forms that indicated increasingly centralized control, such as among the Moche remnants in the Moche Valley that regrouped into what became the Chimor kingdom three miles northwest of Trujillo (850-1470 CE). The Chimor kingdom built upon everything 3,000 years of irrigation technologies and Moche ideas about visual programs and social organization had to teach to accomplish the first engineering state in the Americas at their capital, Chan Chan, where during the Imperial Period the leaders were still adorned with the Twisted Gourd of their ancestors rendered in gold (example: ML100006).

While Chimor art adds little more to what the Moche contributed in terms of understanding Twisted Gourd symbology, Chimor technology does confirm an important aspect of the water cult’s ideology and ritual. Since the Twisted Gourd first showed up in 2250 BCE associated with a shamanic figure at one of the first places in the New World to rely on irrigation to produce cotton, this suggested that 1) the idea of the Milky Way as a serpentine river of life, 2) natural terrestrial serpentine water features described as “glass rivers,” and 3) engineered water features achieved through organized labor were related.

Additional evidence of what tinkuy meant in a ritual water setting comes much earlier and a little farther north with the building of the monumental Cumbemayo Canal at Cajamarca ca. 1500 BCE as a sacred landscape associated with the Chavin/Cupisnique phase. The canal could have had some practical significance in terms of water supply, but the fact that it was relatively short and built to flow past symbol-laden sacred caves suggests a deeper ceremonial significance (Jones, 2010:chap.4).

On a ritual basis, at Cajamarca it is clear that priestly specialists interacted with water that flowed down through outdoor canals and encountered diversions that caused the water to change course and imitate the movement of a serpent, thereby creating a ritual tinkuy. In fact, those diversions were shaped much like the design elements of the Twisted Gourd, which suggests the symbol itself was not just a visual metaphor but rather had a like-in-kind power of the serpent. When the word tinkuy as Rick uses the term (Rick, 2017:43) is applied to ritual where humans and physical water systems meet, this potentially violent but necessary encounter between the natural serpent river meeting the constructed serpent river is the reference. The idea was to tame the encounter enough through like-in-kind ritual symbolism to reduce the destruction. But with that kind of tinkuy might also come sun,- moon,- or starlight on roiling water, and perhaps even small rainbows could have been generated that would be interpreted as a divine gift of sami (vital essence) for the well-being of the community.

Cumbemayo Canal, Cajamarca, Peru. To get a sense of the tinkuy in action at the monumental water installation at Cajamarca, examples of the type of diversions used to tame water flow included a form of the serpent, the stepped fret, placed near a symbol of the triadic world, the stepped triangle, both of which were associated with a sacred cave laden with what appear to be drawings of the sky or perhaps dark-cloud constellations used during water rituals (see the preserved drawings of the symbols– note the incised crosses–and the plan of the canal, Jones, 2010.

A tinkuy with water takes several ceremonial forms. In southern Peru traditional communities still ritually celebrate water as the medium that connects the worlds (Quechua: pachas) with a ceremonial drinking vessel for corn liquor called the paccha where, like the serpentine canal, a serpentine channel mirrors the bicephalic water serpent (Allen, 2002;fig.11) set within a field of stars:

When it comes to getting down to the ancient core of ideas that drew people into settled, hierarchical communities the idea of tinkuy, the basic construct of how it was that life materialized out of a surrounding spiritual realm and how this idea was materialized in ritual landscapes, is foundational. The idea of tinkuy infers motion, which leads to ideas of changes in color, luminosity and directionality as the result of an encounter. The fact that the earliest civilizations in Peru, with type sites at Chavin de Huantar, Cajamarca, and Chan Chan, up through the construction of the labyrinthine sacred cave underneath the Temple of the Sun at Teotihuacan c. 100 CE, which in every way reflected the tinkuy ideology of Chavin de Huantar, strongly suggests that this is the case (Markman and Markman, 1994: Part II(6): Spatial Order). Furthermore, there is interesting evidence that these large ceremonial centers may not have developed out of a growing sphere of regional influence related to agricultural production that might suggest some form of political and/or religious consensus but rather the building of a center that centralized ritual instigated social stratification as a means of regional development, which was associated with increased social violence (Nagaoka et. al, 2017).

A Puebloan Case Scenario for Tinkuy Water Ritual

On a practical level smaller ritual water projects like the Cumbemayo Canal may have formed the technological basis for the Chimu to divert the Chicama River from 50 miles north of their location into their canal system 2,500 years later, that is, around 1000 CE. Between those two examples, or three if Chavin’s ritual landscape is included, we can place the Chacoans of the 9th-12th century CE, who also had an elaborate water catchment and diversion system in a semi-arid environment, to see what was important to water cult ritualists.

Between the water cult’s southern expression in northern Peru and northernmost expression in the American Southwest on the Southern Colorado Plateau, we see the arrangement of sacred water running through a ritual landscape and past an ancestral huaca where encounter with the water serpent as a river occurs. Huaca is a god house and, with an apical founder and a dozen or more of the Chaco lineage buried at Pueblo Bonito next to a serpentine water feature like the Chaco River, it fits the definition of a god house. The place where X marked the crossroads of the Great North Road next to Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon follows the pattern of that type of tinkuy ritual landscape.

This is important in light of the fact that the terrestrial north-south is equivalent to the celestial N-S axis mundi that extends from the North Pole through the archetypal mountain/cave as the centerplace and to the South Pole in the underworld. This also argues for the fact that this ideology was developed in north-central and central Peru, since, again looking north, the pole star and the black hole in which it is located (a shamanic portal) is only clearly visible between December and March in southern Peru.

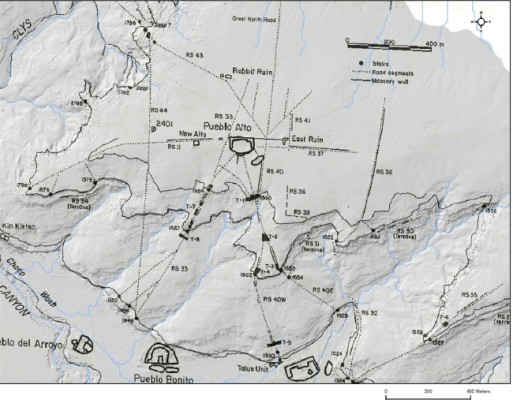

Left: Chaco Canyon Great Houses, Great Roads and the Chaco River and wash meet in Downtown Chaco centered around Pueblo Bonito, where the Strombus was buried with an ancestral member of the old Bonitian dynasty c. 774 CE (Heitman, 2015:221; 2-σ range of 690–873) in a crypt along with thousands of pieces of turquoise (like-in-kind with water). Image abstracted from Kennett, D.J., et. al, 2017:fig.1.

Right: Pueblo Bonito pottery cosmogram c. 1000 CE, a quartered bowl with two black bicephalic serpent scrolls, two “charged” classic Twisted Gourd connectors (serpent scrolls: see Connections), and four tau-shaped symbols at the intercardinal directions that in Maya art are diagnostic for the sun god (Schele, 1976). Notice the N-S and E-W orientation of the connectors. Image courtesy of Smithsonian’s Anthropology Digital Collection #A336324, available online.

The image to the left from Pueblo Bonito is very similar to the pattern in the previous image. There are a number of versions of the same pattern in the Smithsonian’s digital database and it remained part of the visual program of several groups in the post-Chacoan dispersion. The pattern has both dextral and sinestral versions, which suggests that something changes, as in the movement of the Milky Way as it flips from a position above the ecliptic to a position below the ecliptic at the solstices (Fig. 2). Besides the Milky Way, the rather spectacular way that Draco, the polestar, and the Dippers were visually poised over the horizon of the Great North Road on the winter solstice in the context of the ritual importance of the Zenith-Nadir axis for the tinkuy suggests a rather spectacular venue for celestial pageantry and a hierophany provided by the water wizards of Chaco Canyon.

The same design set in the context of the checkerboard Milky Way that is slanted in the diamond pattern (sky serpent) (tDAR Mimbres Digital Database, Galaz Style I 2259, 750-1000 CE) confirm that the design intends to infer sky, snake and rotation. Taken together these designs that are shared between Pueblo Bonito and the Mimbres Mogollon at the Galaz site strongly suggest that these swastika-type moving images that rotate around a Center intend to represent the Dippers rotating around the celestial House of the North that was occupied by Four Winds, the Plumed Serpent, as the zenith of the axis mundi.

View of the Milky Way over Chaco Canyon Facing South.

Left, top, Dec solstice; June solstice below. Right, top, March equinox; Sept equinox below.

When the first phase of Pueblo Bonito was built c. 850-860 CE the C-shaped block of rooms was oriented to the SSE, an intercardinal direction oriented to the sunrise position of the December solstice sun (Munro and Malville, 2011). When Pueblo Bonito was enlarged during the building boom between 1030-1130 CE, the building was repositioned to the cardinal directions and the former SSE axis then faced due south, i.e. like Monte Alban. With bilateral symmetry oriented to the cardinal directions, the center of the building aligned with the Great North Road, i.e., the celestial N-S axis mundi. The intercardinal path of the sun on the December (SE-NW) and June (NE-SW) solstices form the conceptual quartered X over Chaco Canyon when the two paths are overlaid. Images 1-4 above, captured with Stellarium software, show the position of the Milky Way on the solstices and equinoxes at the time Pueblo Bonito was first built.

Chaco Canyon, Winter Solstice Dec. 21, 860 CE

Above: Overhead, as the winter solstice begins, the Milky Way, which began the day lying along the eastern horizon, has by midnight stood up to cross the ecliptic (E-W orange line).

Below: Looking North, a detail from the larger image shows Draco plunging into the horizon above the Great North Road.

The whole purpose of ritual is to connect the three realms, where a tinkuy as a simultaneous catalytic encounter can occur. If we recall that the realms have mirror images, what is happening in the night sky is reflected in the events of the daytime underworld. That is why the water road, the ritually powerful light-water tinkuy encounter, is functionally the Zenith-Nadir axis that connects the night time celestial Above with the daytime celestial Below through the centerpoint of the earth. Functionally, this means that the cross seen in the sky above is not conceptual at the moment captured in this image but rather “real time,” because the Milky Way serpent encircles the earth, that is, it is always present in the day sky and as the underworld river of life. Mirror images in the Above and Below realm of the serpent, connected by the North-South ritual axis, simultaneously would form a dynamic cross, a tinkuy. The arms of the cross in the pottery design are evenly offset from each other, which is what Nadir-Zenith mirrored images would look like.

The whole purpose of ritual is to connect the three realms, where a tinkuy as a simultaneous catalytic encounter can occur. If we recall that the realms have mirror images, what is happening in the night sky is reflected in the events of the daytime underworld. That is why the water road, the ritually powerful light-water tinkuy encounter, is functionally the Zenith-Nadir axis that connects the night time celestial Above with the daytime celestial Below through the centerpoint of the earth. Functionally, this means that the cross seen in the sky above is not conceptual at the moment captured in this image but rather “real time,” because the Milky Way serpent encircles the earth, that is, it is always present in the day sky and as the underworld river of life. Mirror images in the Above and Below realm of the serpent, connected by the North-South ritual axis, simultaneously would form a dynamic cross, a tinkuy. The arms of the cross in the pottery design are evenly offset from each other, which is what Nadir-Zenith mirrored images would look like.

Ritually, once the waters of the cosmos are connected, that is, once the cardinal and intercardinal directions or “roads” of the waterworld (bicephalic serpent) are hooked up however that is conceived, the Zenith-Nadir axis through the centerpoint is the tinkuy that connects what is known throughout Mesoamerica as the House of the North with the underworld. That is when the Milky Way is in a N-S position twice a year at the solstices and becomes the axis mundi or World Tree, aka Wakah Chan, when its tree canopy is the House of the North and its roots are in the underworld according to the Maya of the Yucatan Peninsula (see Maya Connection for a detailed case study). This is also called the Water Tree in northern parts of South America. The Milky Way does happen to cross the solar path of the ecliptic at those times, but it isn’t known with certainty that that was the necessary point that represented the “light” of the light-water tinkuy. What is certain is that in terms of their triadic cosmology and the sky-water realm of the bicephalic serpent, when the Milky Way was in the position of the “standing up sky” the N-S celestial axis always connected a night time Milky Way Above with a daytime sky and the Sun Below. That was the path of the newly deceased, shamans, and ancestral spirits.

Left: ML002902. The sign for the House of the North is represented by the two-color cross with eight partitions, which signifies the cardinal and intercardinal directions. See also ML002382, ML004018, ML002564.

Right: ML002904. The House of the North with a serpent formed out of the two-color bars of the Milky Way (pattern for Milky Way as a sideview; see Checkerboard). The presence of the chakana suggests that the N-S tinkuy connects the House of the North with a House of the South in the underworld. The chakana therefore represents the ultimate tinkuy, the connection along the ritual celestial N-S axis of the Houses of the underworld, earth and sky, where the House of the North is the zenith, the House of the earth the mountain cave, and the House of the South the primordial underworld ocean. In this sense, then, the definition of chakana as “stair, ladder, and crossroad” is applied here as a staircase between worlds shared by priests, ancestors and nature powers.

ML012189, a warrior with a Milky Way (checkerboard) helmet and the House of the North shield with the tinkuy chakana. Again, this image suggests that the chakana is the culmination of light-water tinkuy ritual that completes the connections to open up the portals for shamans, the water spirit, and the ancestors.

ML012801. A special category of priests called the “tonsured” priests (ML search term tonsura) shows one with the Maltese cross and coca-chewing paraphernalia. The archetypal animal connector in the triadic cosmos from the priest’s tunic as shown above in detail mixes the powers of the feline (mountain-cave, centerplace), the bird (sky, Above), and the serpent (Below, all realms). The four green circles around the cross constitute the intercardinal directions. In addition, according to the curators at the Museo Larco, the “turquoise eye is at the same time of the feline and of the bird that projects the beak backwards [a bird nahual]. The cat’s tail and hair extend backwards like snakes. The gods and supreme leaders adopt the features of cat, bird and snake.”

Above: Pueblo Alto c. 11th century (Mathien and Windes, 1987:fig.). “Backward-looking” archetypal animals are shamanic in nature as the nahuals of a water wizard (see discussion in Jones, 2010). In the image above, iconic Andean connectors (see Connectors) are positioned to infer a backward-looking bird and horned serpent bicephalic bar which, in the triadic cosmic structure, constitutes the ritually important celestial N-S axis that connects all the realms of the water world. In light of the fact that the Chaco signature, Andean water connectors, and the checkerboard pattern comprised the art of the residents at Pueblo Alto, this design was intentional. The bowl also appears to represent four tinkuy events where the N-S axis was ritually animated. If the concentric rings were to be vertically and diagonally connected, this would also represent the Maltese cross in eight sections.

Above: Pueblo Alto c. 11th century (Mathien and Windes, 1987:fig.). “Backward-looking” archetypal animals are shamanic in nature as the nahuals of a water wizard (see discussion in Jones, 2010). In the image above, iconic Andean connectors (see Connectors) are positioned to infer a backward-looking bird and horned serpent bicephalic bar which, in the triadic cosmic structure, constitutes the ritually important celestial N-S axis that connects all the realms of the water world. In light of the fact that the Chaco signature, Andean water connectors, and the checkerboard pattern comprised the art of the residents at Pueblo Alto, this design was intentional. The bowl also appears to represent four tinkuy events where the N-S axis was ritually animated. If the concentric rings were to be vertically and diagonally connected, this would also represent the Maltese cross in eight sections.

The inset image to the left from the contemporaneous Zuni Village of the Great Kivas (Roberts, 1932:fig.30) shows a similar concept of the bird-serpent N-S axis and is very close to the Peruvian original.

Left: Hopi stone cloud blower with Maltese cross from Hopi Snake Dance (Bourke, 1884:pl.XX). The Snake Dance is held in August, which suggests there were occasions outside of the solstices and equinoxes during which the light-water tinkuy between the Zenith and Nadir could be established.

No matter how you construct it, there is a cross with a centerpoint in the sky over Chaco Canyon on the night of the winter solstice, which is reflected in the quartered design with a centerpoint on pottery from Pueblo Bonito as shown above. The design has four diagnostic tinkuys (two black within white bicephalic serpent bars, plus two standard interlocked tinkuys) and four T symbols, where T is the wind symbol of the Mesoamerican Feathered/Horned Serpent. The latter suggests that by 1000 CE the Chacoan’s serpent ideology had acquired a distinct Teotihuacan-Toltec influence, perhaps at the time Pueblo Bonito was re-aligned to the cardinal directions. Although Teotihuacan declined by c. 650 CE, its leaders instigated the cult of the Feathered Serpent movement in Mesoamerica, and the so-called Toltecs adopted their ideology and iconography (Jansen and Perez, 2007).

As part of the ceremonial context, the three places in Downtown Chaco where “weeping/drooling” (like-in-kind water to attract rain) human effigies have been found so far are Pueblo Bonito, Pueblo Alto, and the late Bonito phase community of Bis sa’ani, which is located overlooking the Escavada Wash east of Pueblo Alto and about eight miles from Pueblo Bonito. The three Great House locations in Downtown Chaco that possessed Spondylus shell, the female bivalve complement to Pueblo Bonito’s Strombus trumpet, included Pueblo Alto and Pueblo del Arroyo, which is located directly across from Pueblo Bonito on the Chaco Wash (Mathien and Windes, 1987:426).

The Great North Road as a Tinkuy Ritual Landscape. The interpretation of Downtown Chaco as a tinkuy ritual landscape is supported by data from Wills and Wetherbee (2012), who shed new light on irrigation strategies in Chaco Canyon and suggested that many Chaco roads may have been used as water control systems rather than as transportation routes. The need for water control was of course practical, but in Amerindian thinking the practical always has its roots or complement in the unseen world, which is represented visually through the reflective art of contour rivalry and modular line width.

Their analysis of “Downtown Chaco” with a focus on the Pueblo Alto community also suggested that the Great Houses were sited to control water run-off and may have served as community-based agricultural production zones. In the next figures notice that with the realignment of Pueblo Bonito to cardinal south it forms the ritually important North-South axis, the pivot of the four quarters in terms of Milky Way/serpent ideology, albeit with a slight twist as is appropriate for tinkuy serpent iconography, and Pueblo Alto (built 1020-1050 CE) is sited at the middle of that axis. If that is the case, it may represent the convergence of the “old Bonitian” ceremonialism of Pueblo Bonito with the new boom in building construction that constituted the “Chaco Phenomena,” when Pueblo Bonito was redesigned and Pueblo Alto was built.

“Downtown Chaco.” Map from Wills and Wetherbee, 2012:fig.1. Notice that Pueblo Bonito is the center common to both a SE-NW cardinal axis extending from Fajada Butte to Penasco Blanco, the path of the sun at the winter solstice, and a N-S ritual axis extending from the Great North Road through Pueblo Alto and Tsin Kletzin.

The Big Dipper. Another celestial feature that was important in the rain calendar of the Andeans and is a distinct feature of the Chacoan night sky at the solstices is the Big Dipper. According to Maria Reiche, who spent her career studying Nasca geoglyphs, also a Twisted Gourd culture, in southern Peru in terms of their relationship to the night sky (Sparavigna, 2012):

“The figures indicated the division of the year by way of constellations, with respect to their positions at night. The most important epoch of the year was, until now, December. This was the month the rivers would fill to the brim with muddy water that brought life to the fields. Now this has all stopped. There is an eternal drought here due to the contamination of air quality preventing the clouds from reaching the high mountains to fill the rivers. Years ago one could see the people making furrows in the fields to prepare for the arrival of the water. In ancient times they knew when to begin this labor … Here the Big Dipper (our Big Bear) announces the water. This constellation is only visible between December and March and is seen here upside down with the handle curved upward. It’s possible that the Dipper was represented by one of the large drawings – the monkey. … and several straight lines point to the rising and setting of the largest star in the Dipper in the year 900 AD.”

“Downtown Chaco,” i.e., the Great Houses surrounding the Great North Road and Pueblo Bonito, has long been thought to have been a ceremonial center. Given how little acreage Chacoans actually farmed, Chaco Canyon may have served as a regional demonstration center for irrigation and agricultural methods, possibly with ceremonial tinkuy encounters that were associated with high maize yield from small plots credited to the efficacy of water cult ritual. What was shown to be effective in attracting pilgrims and building social cohesion throughout the Classic-period dynasties of Mesoamerica and South America was pageantry, especially celestial pageantry, ritual competition that indicated the will of the nature powers (Friedel et. al, 2001), and consumption rituals, all of which are indicated for the Moche (see Ceremony) and all of which may be indicated for the Bonitians. These ceremonial occasions were also opportunities for pilgrims to pay their “tax” for spiritual services through labor exchange and more material contributions, such as the turquoise male #14 was buried with in the Bonitian’s crypt.

This work is under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 Unported license . Suggested citation for text: Devereaux, M.K., 2018. Twisted Gourd, The Symbolic Language of the Precolumbian Rainmakers, Part I. The Origin of the Twisted Gourd Symbol Set in an Ancient Andean Ecocosmovision of the Terrestrial Watershed, http://www.thetinkuy.wordpress.com.