ROUGH DRAFT

Purpose of the Tinkuy Blog

Significant Research Findings

Please report broken links to thetinkuy@gmail.com

Preface

Outside of Time: The Royal Art of the Liminal Realm

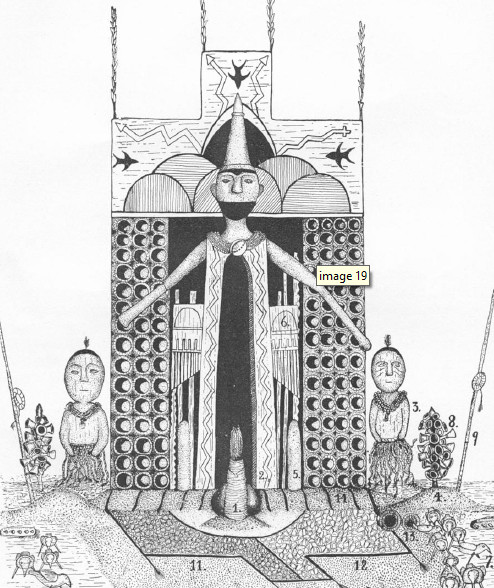

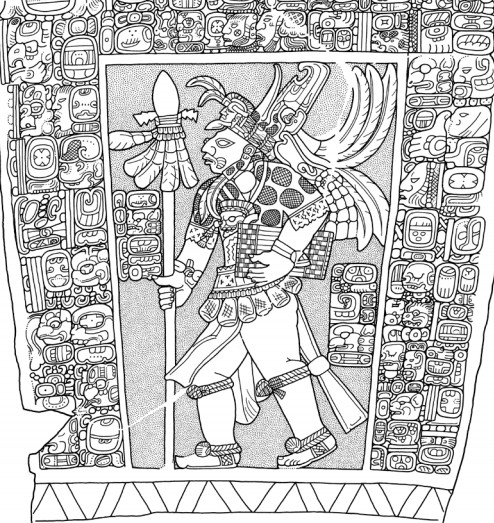

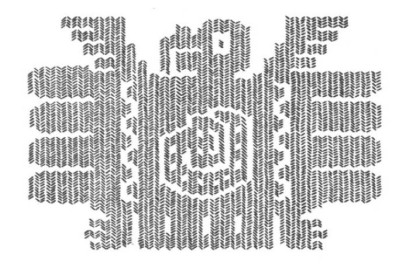

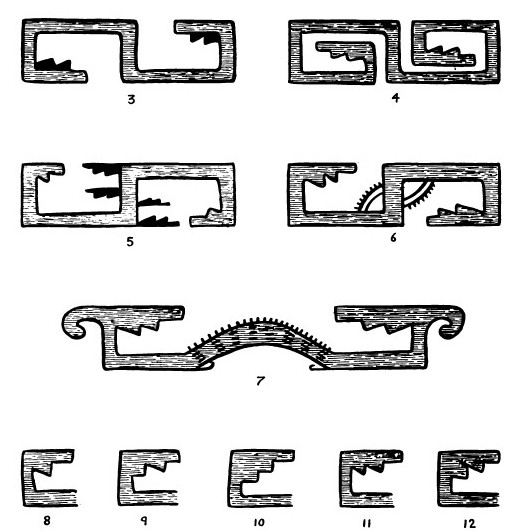

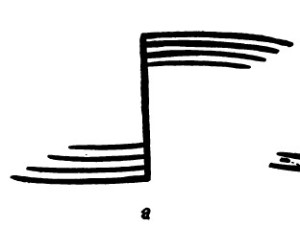

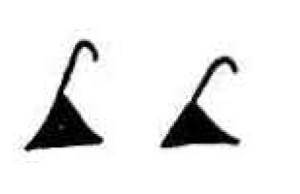

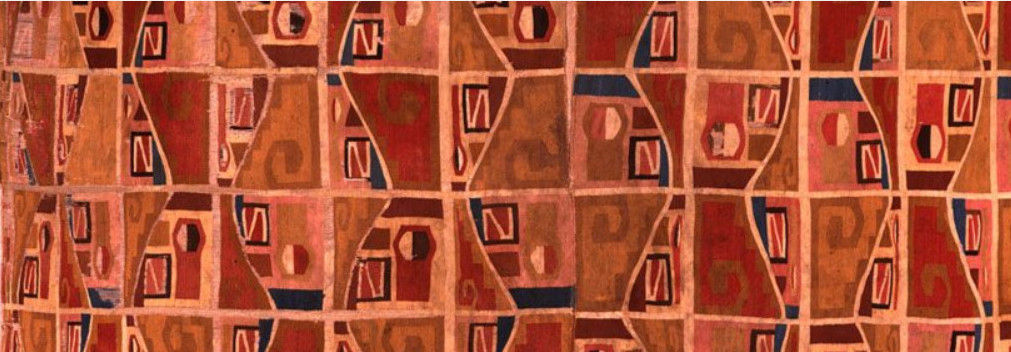

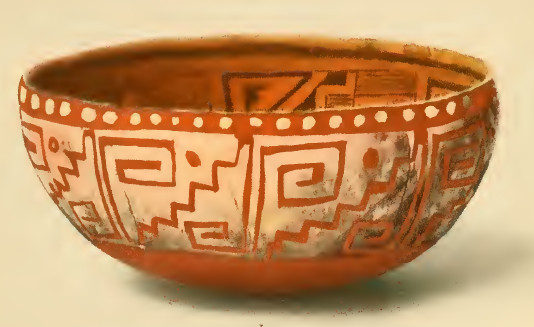

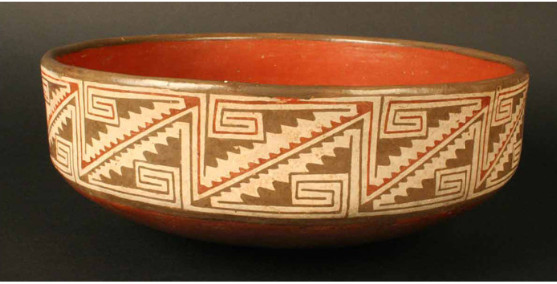

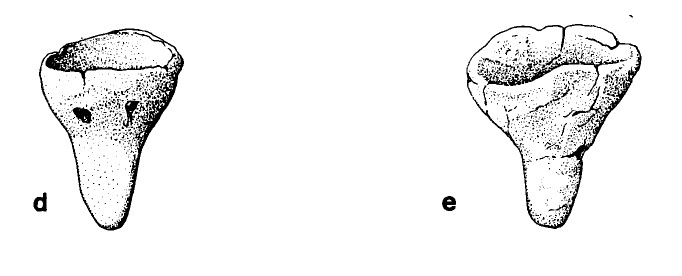

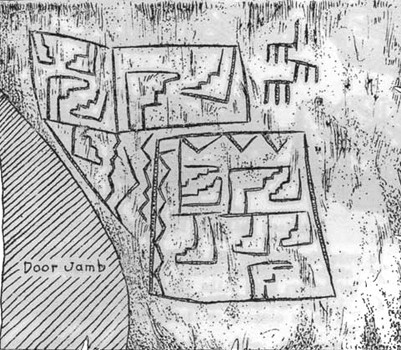

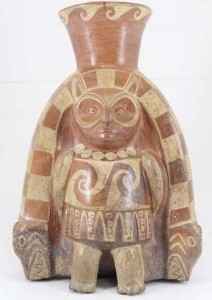

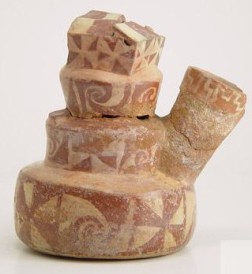

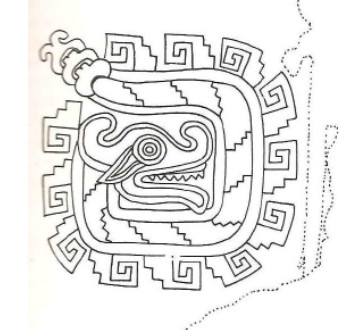

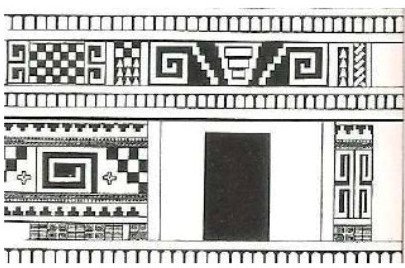

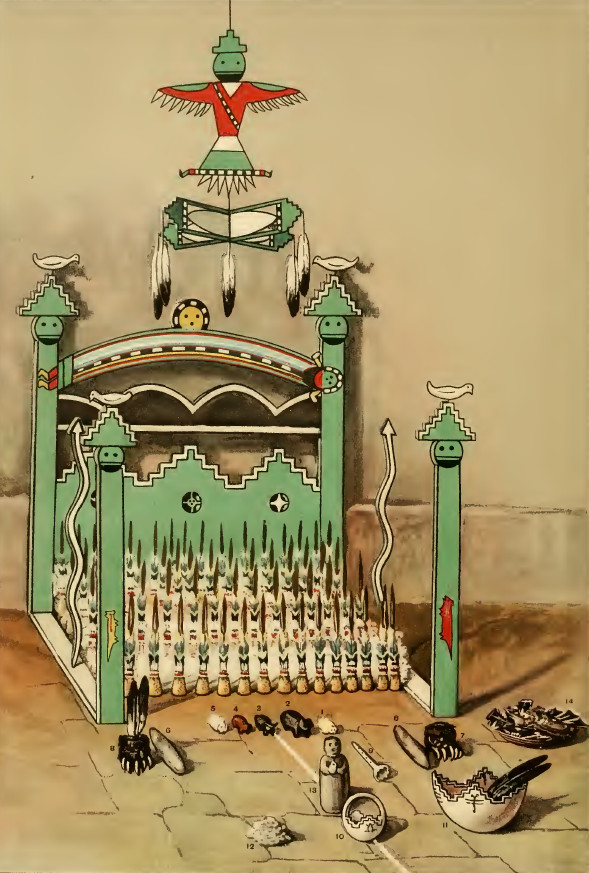

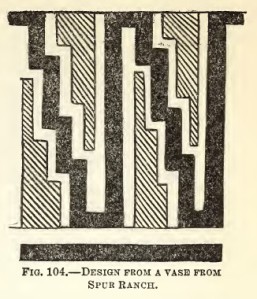

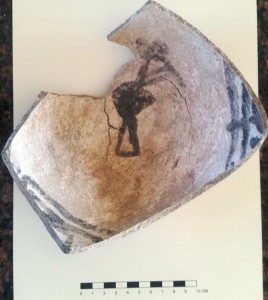

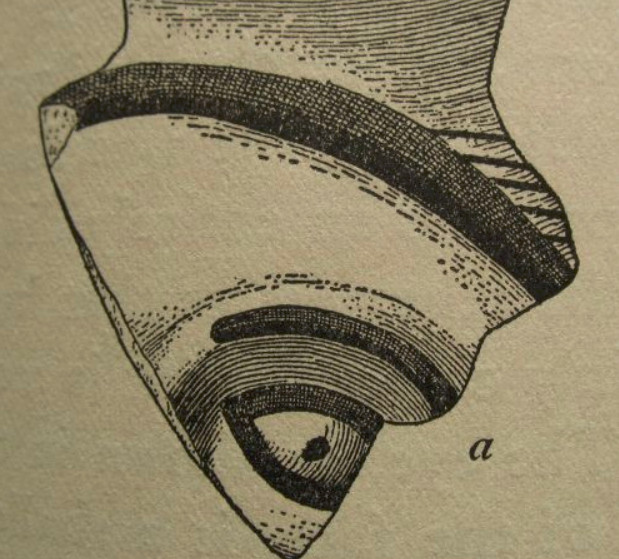

Above: The mythological Lightning Serpent as an integral part of the mythological centerplace– the Snake-Mountain/cave-Cloud/lightning ideogram– is the Twisted Gourd symbol (xicalcoliuhqui) found carved into a ceremonial gourd at Norte Chico, Peru, 2250 BCE , alongside (left) the earliest known depiction of the Andean Staff god, the main Andean deity for thousands of years (Haas et al., 2003; summa, Piscitelli, 2014; Staller, Stosser, 2013). The Twisted Gourd design is stylistically referred to as Greek keys or stepped frets in the tDAR Mimbres Pottery Digital Database: see 2085, 2277, 8014, 3665), which, 3,000 years after Caral-Supe, appears among the Puebloans of the American Southwest at Pueblo Bonito and Mesa Verde as the northernmost expression of the ideology associated with the religious-political authority of Twisted Gourd symbolism. As in Peru, the xicalcoliuhqui symbol at once signified 1) a sacred location for ritual where heaven, earth, and underworld met at a centerpoint, 2) legitimate rule, and 3) a cosmology that mapped hereditary leadership to the timeless liminal realm of creative power. This legitimization was founded upon origin stories of how the world of the creator-ancestors was formed by the thoughts of the cosmic Serpent creator, the unifier of heaven and earth, which manifested visually as the sinuous dark background of the stars of the Milky Way. Caral-Supe, part of the Norte Chico archaeological zone that comprised four river valleys, appears to have been abandoned c. 1800 BCE for reasons unknown, but the fact that its Twisted Gourd symbol set continued to dominate visual programs of social elites in many advanced cultures thereafter, including the Inca, Maya, Zapotecans, Puebloans and Aztecs, is a testament to the enduring influence over time of how its symbolic significance was transmitted through the ontological narrative of ruling figures, much like a trademark. (Photographer: Jonathan Haas, Fields Museum. The image of the Twisted Gourd symbol-the xicalcoliuhqui- has been rotated 90 degrees and slightly enhanced by contrast to eliminate glare.)

The Xicalcoliuhqui: Present at the Beginning of Civilization in the Western Hemisphere to Signify a Religious-Political Worldview of the Reciprocity Between Visible Life and the Unseen World of Ancestors

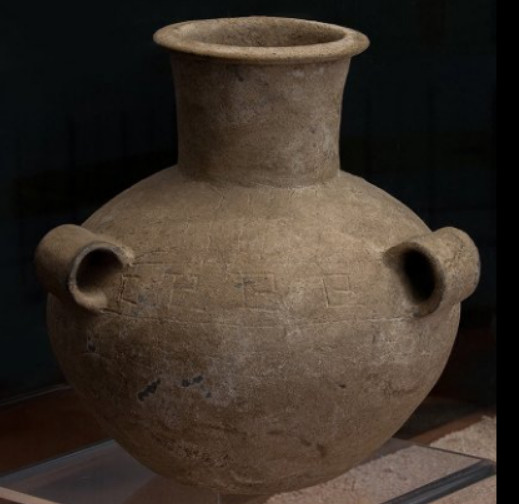

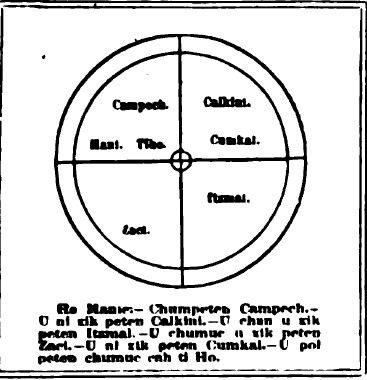

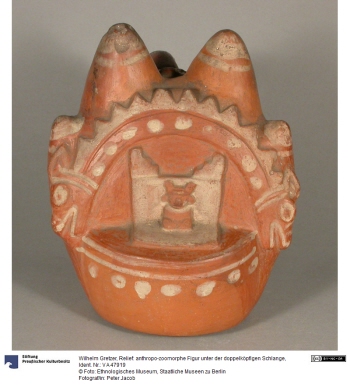

The Norte Chico Archaeological Zone where the earliest known xicalcoliuhqui (twisted gourd) was found houses the remnants of the Caral-Supe civilization of north-central Peru, which, dated to c. 2600 BCE, is the earliest known civilization in the Western hemisphere. Its pyramids are as old as ancient Egypt’s. What the xicalcoliuhqui (twisted gourd, stepped pyramid/mountain) signified was the unity of the Lightning Serpent (cosmic serpent, Feathered Serpent) with a mountain of origin through which the axis mundi passed and at which dynastic lineages ruled. The power of imperial authority in both ancient and modern societies has been routinely justified as divinely sanctioned and continuous from the creation of the universe- as part of a timeless order- through the performance of rituals that invoke, reenact, and perpetuate the process of creation in the making of the present world.” These human heirs of transcendent mythological creators used “architectural forms that framed the ruler within a tableau of ordered creation and evoked a specific mythology as a tool of statecraft” (Hoopes, 2009: 247).

What the xicalcoliuhqui (twisted gourd, stepped pyramid/mountain) signified was the unity of the Lightning Serpent (cosmic serpent, Feathered Serpent) with a mythological mountain of origin through which the axis mundi passed and at which dynastic lineages exerted authority over local populations.

“The power of imperial authority in both ancient and modern societies has been routinely justified as divinely sanctioned and continuous from the creation of the universe- as part of a timeless order- through the performance of rituals that invoke, reenact and perpetuate the process of creation in the making of the present world.” These human heirs of transcendent creators used “architetural forms that framed the ruler within a tableau of ordered creation and evoked a specific mythology as a tool of statecraft” (Hoopes, 2009: 247).

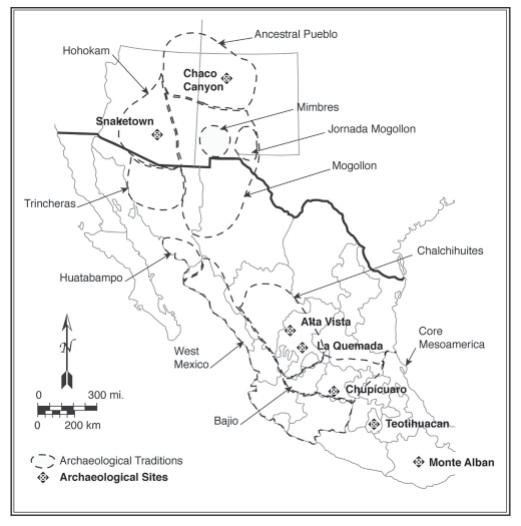

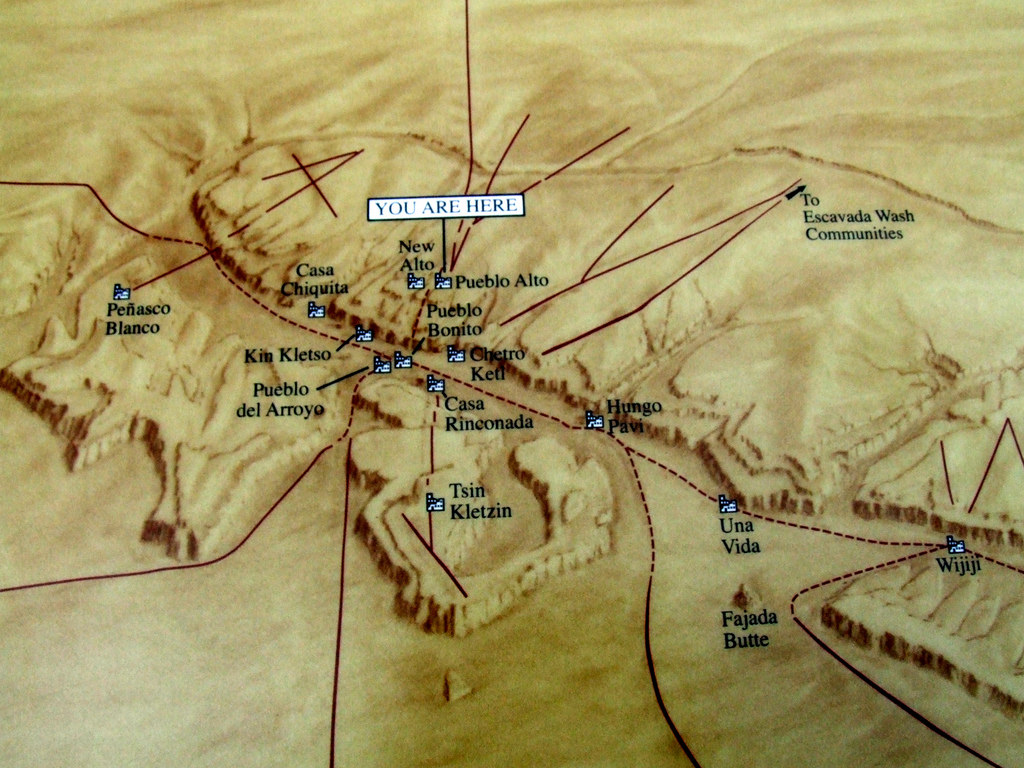

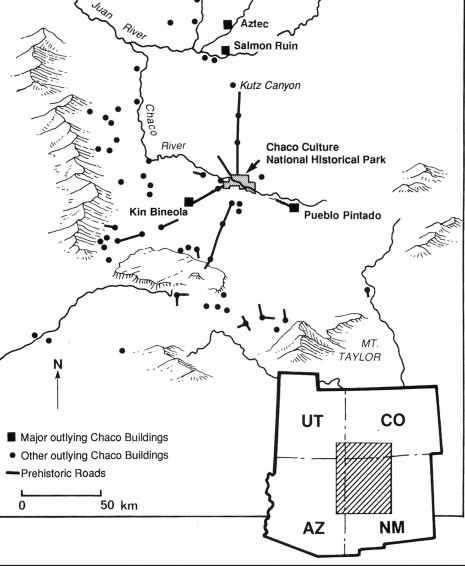

By linking Peruvian, Mesoamerican, and Puebloan art and iconography over time with ethnographically derived cultural data, for the first time there is a firm archeological foundation upon which to understand the Mesoamerican context of the rise of Puebloan culture and the phenomenal development of the Chaco Canyon civilization in the Four Corners region of the American Southwest

What we can immediately recognize in the figure of the Lightning Serpent- literally a “feathered” (sky, lightning) Serpent that ruled the Above, Center, and Below as the axis mundi of a triadic universe- is the trinity of mythological animal lords that governed and unified the triadic cosmic realms known to the Cupisniqui (c. 1200 BCE) and Moche (c. 100 CE) Peruvians and the Anasazi (ancestral Puebloans c. 600-750 CE) of the American Southwest in the context of Twisted Gourd symbolism. This suggests that in time we may be able to project the meaning of the Twisted Gourd symbol through the many parallels gleaned from Moche, Maya, Inca, and Aztec art back onto this most ancient form of the Andean Staff God c. 2250 BCE–the saucer-like eyes (Snake, pools of water, owl), fangs (Jaguar fire/sun god), wing-like headdress (principal Bird) in the context of Twisted Gourd symbolism. In the stepped fret of the Twisted Gourd symbol we note what will become the dominant theme of Peruvian, Mesoamerican, and Anasazi Pueblo art of dynastic families– the prevalence of the dualistic idea of mirrored positive and negative space in twisting forms of the primordial cosmic Serpent that unified the enfolded material and invisible realms through the four phases of water that were distributed throughout the three realms, hence the centrality of the cosmic Plumed Serpent, aka the winged amaru water snake that is seen in art extending from South America to Pueblo Bonito and in the Mogollon cultural sphere, in the myth-histories of the earliest agricultural societies. In effect, while this unity of material and nonmaterial spaces was an attribute of the created world, its highest expression was encoded in the Twisted Gourd symbol as an ideology of legitimate rulership that was vested in dynastic ruling lineages.

In short, the earliest religious impulse in the Americas was a theocratic expression of a widely shared myth-history of what we have come to understand in the modern era as the divine right of kings, who possessed an endowment of spiritual power and wisdom given to hereditary rulers who were thought to have descended from supernatural beings. The fact that similar ideas of a unity of fire-water vested in kingship (by whatever title the overarching ruler-warrior was known) formed the basis of legitimate religious and political authority worldwide attests to the venerable antiquity of the belief that elemental powers possessed by animal gods were inherited by a ruler through his patron deity and primordial ancestor. The probable origin of the idea likely was in ancient shamanic practices that developed into the priesthoods of ceremonial centers of the early agricultural civilizations, such as seen at Chavin de Huantar where the ideology is visually more fully developed by 1200 BCE.

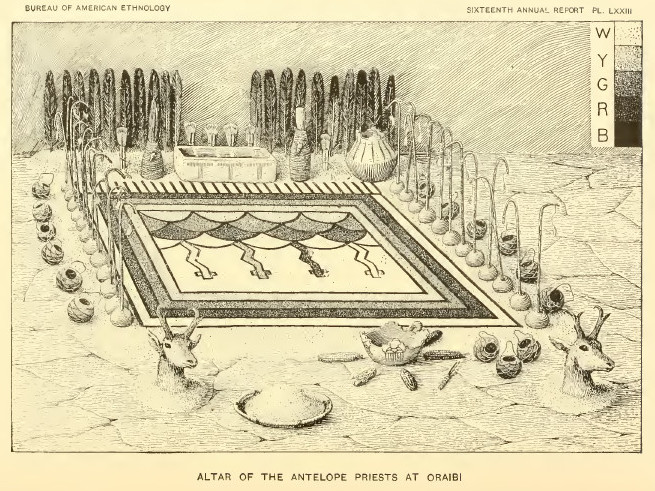

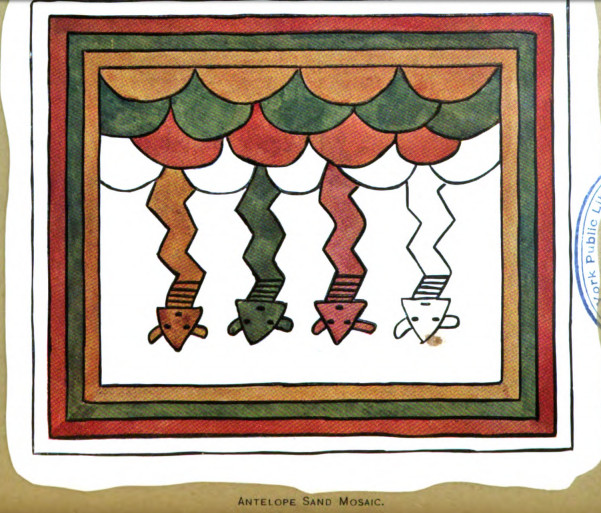

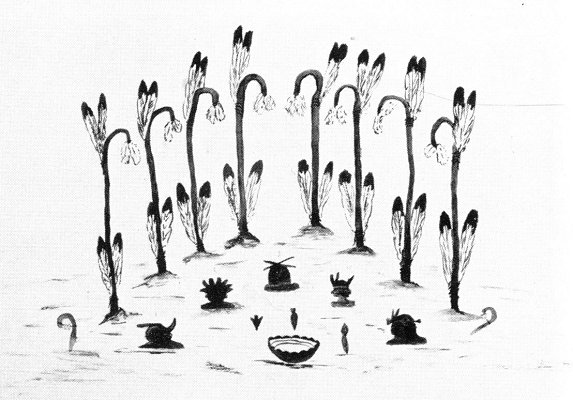

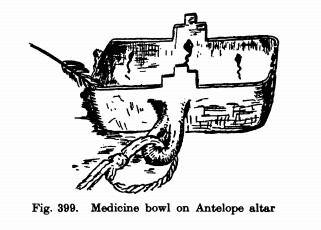

Between the earliest known example of the Twisted Gourd symbol found in the apparently peaceful and female-dominated Caral civilization of Peru c. 2250 BCE and the rise of the Moche where we begin to see Twisted Gourd symbolism associated with the iconography of the warrior priest c. 100-200 BCE, there is scant visual narrative that filled in the knowledge gaps of how the earliest agricultural civilizations formed social hierarchies and defined authority until we get to the Maya divine kings c. 300 BCE-150 CE. It was not until Twisted Gourd symbolism was discovered as the earliest and dominant visual program of the ancestral Anasazi Puebloans in the Chaco civilization of the American Southwest c. 750 CE, in the context of a preserved origin myth and detailed ethnography of ancestral clans and the historical rituals of the Snake-Antelope society, that a deeper understanding of Twisted Gourd symbolism as the cosmogony and cosmology of rulership and social order mediated by divine ancestors could be more fully understood. Among the Puebloans, the autocratic role of the Tiamunyi, the Antelope chief-priest, and his spiritual twin, the Snake chief-priest-warrior called the Tsamaiya (aka Tcamahia), comes to the foreground to unify the powers of water (cosmic Feathered Serpent) and sun (Antelope) in the myth-history of a dynastic ruling family that has survived into the 21st century.

From Formative period Peru to the Toltec Quetzalcoatl of the Mesoamerican post-Classic period, the Twisted Gourd symbol represented the living-dead Ancestors of hereditary rulers by pointing to the cosmology that made them possible, e.g., the Snake-Mountain/cave -Cloud/lightning centerplace, a topocosm where the visible and invisible realms came together as a point of creative origin in the womb/hearth of the earth to validate the authority of hereditary rulers as sustainers of life through reciprocity. The ideogram is at once the ancestral Snake-Mountain/cave and Snake-Cloud/lightning that, as we’ll come to see, represents a conflation of the reality of visible vs. liminal realms with here-and-now vs. mythological time in one location, which extends the identity of the occupants of an ancestral royal house to a place (stepped triangle=pyramid=Mountain/cave) that links them to the origin of nature and its natural processes of light and water that sustain life. At a glance, the privileged occupants are co-identified and co-located with the source of water as both rain cloud (stepped triangle), agency of fertilization (rain, lightning), and primordial ocean, e.g., cosmic Serpent (stepped fret) that existed beneath the terrestrial plane and connected with the earth’s surface through caves, springs, lakes, and rivers. The cosmic Serpent (amaru) was the Milky Way “river” that had its source in the primordial ocean and also, as the source of rain clouds, was also the cloud Lightning Serpent. The importance of the unity of fire and water in the co-identity of the Lightning Serpent and cosmic water Serpent as being central to the constructs of this indigenous cosmogonic order cannot be overstated. As a liminal frame of reference, this ancient Fire Serpent pointed to water as the source of mist (clouds/mountains=stepped triangle, connoting the idea of a stylized cloud integrated with and emanating from the primordial Mountain/cave), with mist being the primordial state of the cosmic Serpent, and hence also associated with the oracular wisdom of priests and the breath of life.

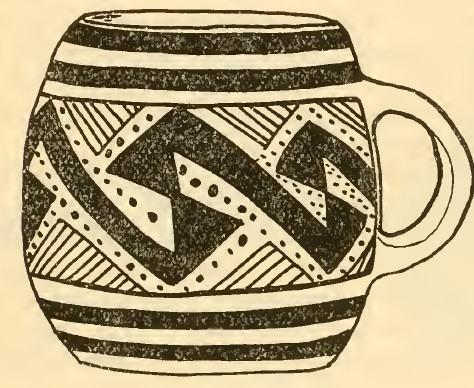

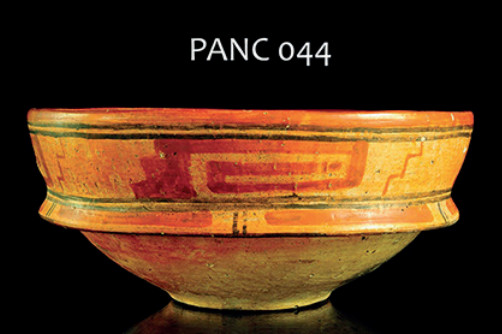

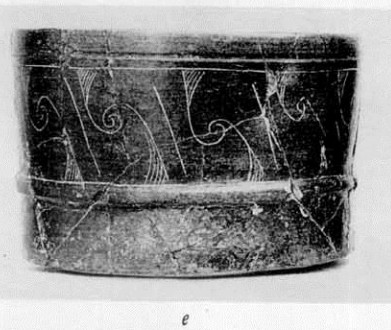

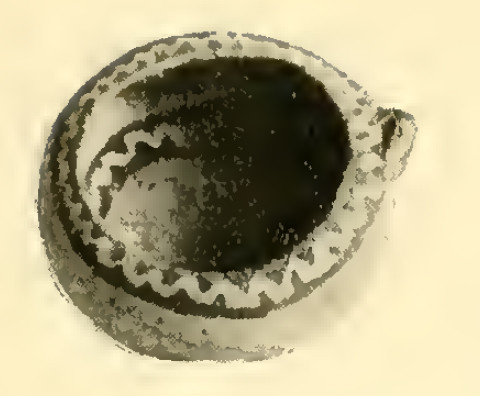

The Twisted Gourd symbol entered what was to become the Maya cultural area by 300 BCE-150 CE as attested by the Chicanel phase vessel shown above from the Lowland Maya late Formative (proto-Classic) Peten region of the Snake kingdom. It was recovered from El Mirador, Guatemala, founded 1000-600 BCE in the El Mirador Basin, arguably the first great metropolis of Mesoamerica in the cradle of Maya civilization (Hansen, 2014). Other examples of the Twisted Gourd symbol on Chicanel pottery were found at Uaxactun (Chicanel phase 350 BCE-250 CE; Longyear, 1942:fig.46L) and in a royal tomb at Nakum (Zrałka et al., 2011) where it covered the face of a social elite. In context on Maya codex-style vases that were later made in the Mirador Basin, the Twisted Gourd symbol was associated with rulers sitting on thrones and receiving homage (K868) or participating in war scenes (K2206) and ritual blood letting (K7433). The Chicanel horizon of the Pre-classic period (300 BCE-200 CE) when the Twisted Gourd symbol was introduced was associated with foundational events of the Maya civilization, which included a new mythology of divine kingship linked to a change in a mythic hearth (“…a theological assertion about the past and a belief in the necessity of fiery, cyclic renewal”) and construction of massive buildings (Houston, Taube, 2008: 129-130). Importantly, the persistence of the Twisted Gourd symbol into the Classic period was included in the “stylistic canons and motifs… [that] served to evoke the hallowed, ancient times of gods and ancestors. These were intentional revivals, rather than survivals of inherited traditions…” (ibid., 131), strongly suggesting that the ancient South American icon conveyed the memory and meaning of the fiery, mythic events of the creation that produced the maize god and the divine progenitors of the ancestral lineages of those who were born to the task of divinely sanctioned leadership.

The Twisted Gourd as Snake Mountain/lightning: The Fertile Womb of the Earth and the Lightning Serpent as the Oldest Religious Paradigm in the Americas

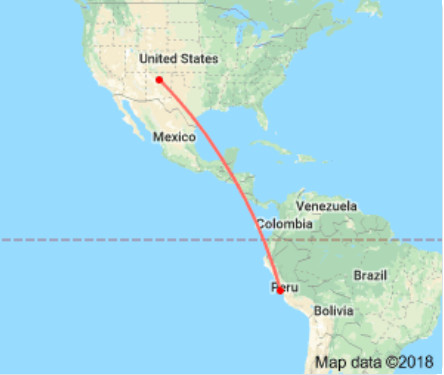

In following one symbol set over a period of at least 5,000 years and a distance of more than 4,000 mi that defined and established a religious-political ideology of divine authority in developing agricultural societies, which extended from the earliest civilization in Peru to the Pueblo communities in the American Southwest, certain shared beliefs within a shared indigenous American worldview emerged. In terms of a universal analogy, the indigenous American worldview saw a creation that began with a union between heaven and earth, and more specifically as lightning striking a primordial ocean that generated an enduring pan-Amerindian igneous : aquatic paradigm of creation.

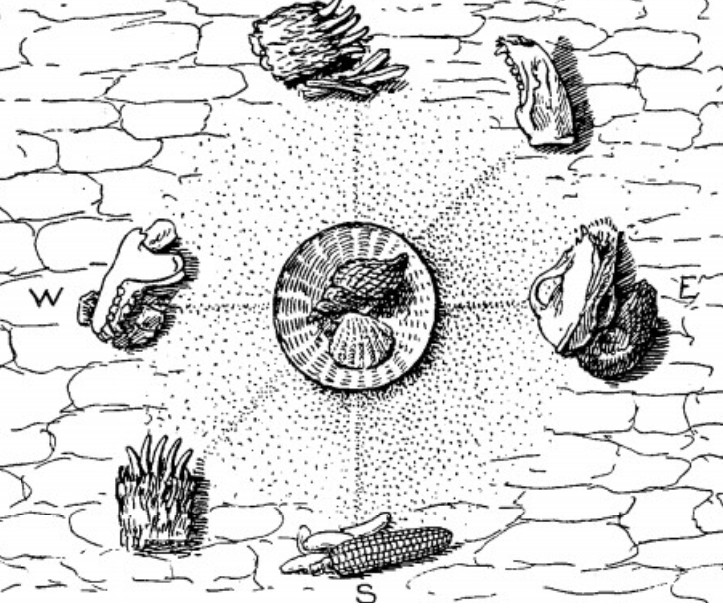

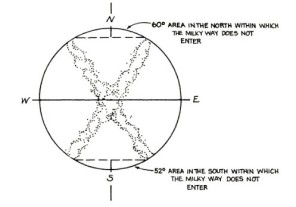

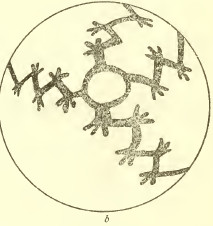

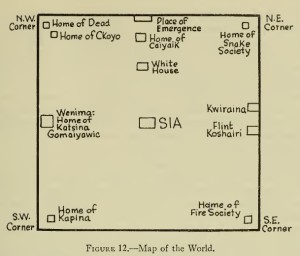

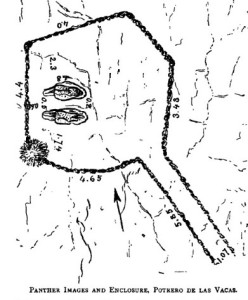

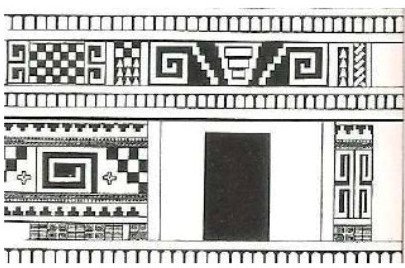

The cosmic Feathered Serpent embodied the igneous : aquatic paradigm through its identity as water and wind (Snake, Milky Way river of life, movement through the six sacred directions, which it authored as the supreme creator deity during the foundation of the earth, and Bird (sky, associated with the sun, fire). The six sacred directions (metaphysical roads traveled by deities) are Above/sky, space; Below/Underworld, and cardinal North, West, South, and East. They meet in the Center, which is a location in the ritually important navel (womb) of the earth that is conceived to be a cave with a cosmic hearth deep within a sacred mountain wherein rivers, springs, clouds, the dawn sun, and, crucially, lightning originate, yielding both the pan-Messoamerican igneous : aquatic paradigm of creation and the design of the Twisted Gourd symbol as a Snake Mountain/cave, a place associated with life, death, and regeneration where deities and revered ancestors commune with elite dynastic ritualists (kinfolk to a tutelary deity who is the father of a dynastic lineage), concerning provision of water, sunlight, .good crops, and fertility. It is important to note that “provision” is a two-way street; humans sustain the life of the deities/ancestors through proper celebratory ritual and sacrifice, and in turn the gods and ancestors sustain earthly life. Briefly, the Feathered Serpent in its role as the axis mundi, which extended from celestial North through the earth’s navel, which was a portal into the Underworld, represents a unity of nature through the observable seasonal movement of the Milky Way river in relation to the path of the sun moving between the intercardinal directions at the solstices. This enduring pattern of order, which associated the sentient powers inherent in natural cycles with legitimate dynastic authority though, can be observed in the art, myth, and rituals along the pan-Amerindian path of the Serpent, e.g., ritual centers where divinely empowered rulership was associated with the Twisted Gourd symbol in a symbolic geometric context that traveled with it from South America to North America, each symbol related to the sacred directions, the functions of which were personified and displayed by dynastic authority figures (checkerboard pattern, quincunx, equal-arm cardinal cross, equal-arm intercardinal cross (soltitial “X”), the overlay of the two crosses within a circle or square, the rotator pinwheel, and the chakana, the latter signifying sacred stepped mountains at the four cardinal points that were connected to the Centerplace and the axis mundi). The idea that a ruler, divinely empowered by kinship with one of the three animal lords that ruled the axis mundi and the cardinal and intercardinal directions, was the basis for political and religious authority that presumably could call upon family relations from the liminal realms of the primordial animal lords– Snake, Jaguar, Bird– to meet the needs of a community for food, water, health, and security. .The ideas associated with the cosmic Snake (Milky Way, water provision, sky realm, wherein the Milky Way river at sunset flowed into the watery underworld, which was contiguous with the sky and also the domain of the Snake) were always mountain-top clouds, lightning, and thunder acting seasonally at the points of the celestial (Above, Below axis mundi) and terrestrial cardinal and intercardinal (soltitial) sacred directions. From the earliest known appearance of the Twisted Gourd symbol at Caral Supe in Peru c. 2250 BCE, its appearance c. 150 BCE -200 CE to signify the Maya divine kings, and its appearance after c. 900 CE among the dynastic family occupying Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon, one characteristic of each of those places as a persistant physical manifestion that appears to have offered visual proof of kinship with the Jaguar/predatory feline Lord of Fire at the navel hearth–the Centerplace– was polydactyly– six toes or fingers.

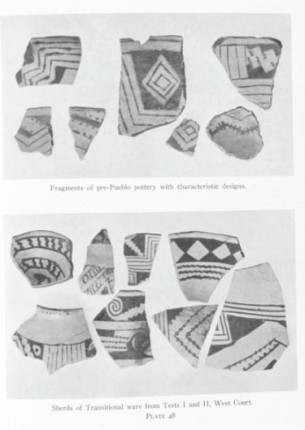

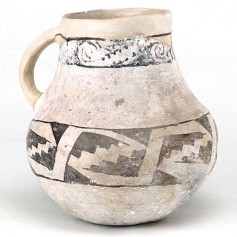

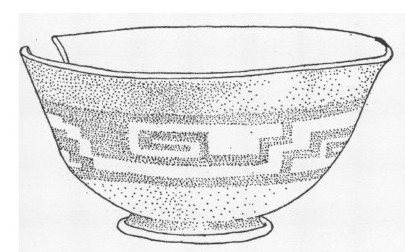

The fire/water paradigm was reflected in the ancestral identity of those who had been born to rule, the priestly and military elites and kings with divine blood who occupied the top tier of developing social hierarchies. In the Americas, the divine ancestry of a figure like a Maya god-king, an institution that emerged in the pre-Classic social context of Twisted Gourd symbolism in Guatemala among the ancient Snake kings, was illustrated through a major patron deity of the divine god-kings, K’awiil, who was shown with the cosmic Serpent as one of its legs and six feline toes on its remaining foot at Palenque. The iconography of royal elites at Palenque likewise showed them with six toes, which pointed to the fact that the infrastructure of the triadic world was sustained by the cosmic Serpent as a trinity of predatory animal lords, the cosmic Snake, Jaguar Sun/fire god, and Principal Bird, a concept of cosmogonic heredity shared by both ruler and his ancestral deity that was first identified in the art of South America. Although polydactyly as an archaeological marker of this ideology of divinely human rulership is by no means completely understood, clearly polydactyly and snake symbolism were symbolic means of mapping the identity of social elites to the imago dei, e.g., the Milky Way as the axis mundi that functioned through the auspices of the Above-Center-Below animal lords of a triadic cosmos, with ancestral ties to the creation of the world and the creator as the basis of their social authority (see Cushing, 1894, for the most detailed description available of the role of the animal lords, e.g., the “beast gods,” in Pueblo directional ritualism). Their very existence was a demonstration of a dimension of invisible powers that generated the theo-drama of a mandated reciprocity between god(s) in the liminal realm and men in the visible world. Put another way, the visible realm represented the dynamic “words” or thoughts of the creator deity, and social elites with kinship bonds to the creator were the vital link between those realms. Wearing or displaying the Twisted Gourd symbol was another, because the symbol represented the ancestral place of origin as the navel womb of the cosmos where the first-born ancestors of dynastic elites emerged during a mythic age. A myth-history of primordial origin extending through dynastic lineages into a present time was the legacy and basis of authority of royal families, a pattern observed among the Moche of Peru, the Maya kings, and the dynasty that occupied Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon. Within a century of the appearance of Twisted Gourd symbolism in Guatemala, it appeared in Mexico as the dominant geometric symbolism on elite crema pottery in Oaxaca (Elson, Sherman, 2007), on Teotihuacan’s diagnostic censers roughly a century later, Mogollon pottery by 650-850 CE, and as the dominant religious symbolism on Red Mesa pottery at Chaco Canyon by 875 CE.

Together, the immediately recognizable archaeological markers of a shared ideology of rulership included Twisted Gourd symbolism, polydactly, and the architecturally advanced Great Houses of centralized authority (formal temples, pyramids, the Pueblo Bonito Great House as a dynastic crypt in Chaco Canyon) in the context of a system of sacred directions (deity roads converging on an archetypal point of origin, the Mountain/cave centerplace) is seen in Peru, Mesoamerica, and the American Southwest by 2250 BCE, 300 BCE, and 750 CE, respectively. This coincided with life-ways that were transitioning into densely populated agricultural communities with market economies living in remarkable urban landscapes designed as sacred precincts that were precisely aligned with celestial bodies. The directions corresponded with the beginning of time and the movement of the sun along the ecliptic. The celestial bodies of mutual interest included the Milky Way, sun, moon, Venus, and the Dippers, all avatars of the cosmic Serpent, aka the amaru, the denizen of the Milky Way that in its standing position was the World Tree. In South America, Mesoamerica and the American Southwest this force of primordial nature, source of water and father of the sun, came to be represented as the Feathered Serpent, the ancestral patron of royal families that embodied command over the sky, terrestrial plane/centerplace, and the underworld of the triadic cosmos. Since the directions were also synonymous with the Ancient (author) of Directions, the Plumed Serpent, the corresponding Western religio-political concept for an overarching mythic representation of materialized eternity would be the Ancient of Days.

At the Norte Chico zone of the Caral civilization in Peru, the earliest complex society of the Americas where the earliest religious icon, the Twisted Gourd, was found, also found was a spiral geoglyph drawn to clearly show the idea of two helical rotations in two opposite directions, an idea that is encoded in the dark-and-light interconnected stepped frets of the Twisted Gourd symbol that represented the spiral interior of a conch shell, the indexical symbol of the Plumed Serpent that was materially present in water and at the same time metaphysically present in the invisible order. The invisible order, which possessed sentience and thought and organized and maintained the visible world, was the basis for rulership, prophecy, and right action. It was also the basis of the necessary reciprocity between gods and humans that sustained the cosmos, a duty for which humans rulers were responsible in terms of proper ritual and sacrifices.

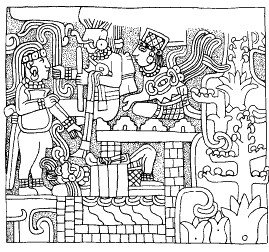

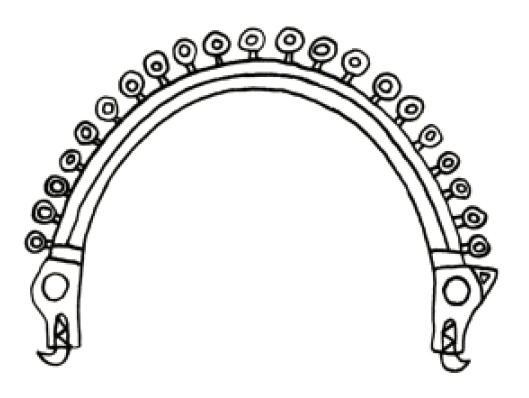

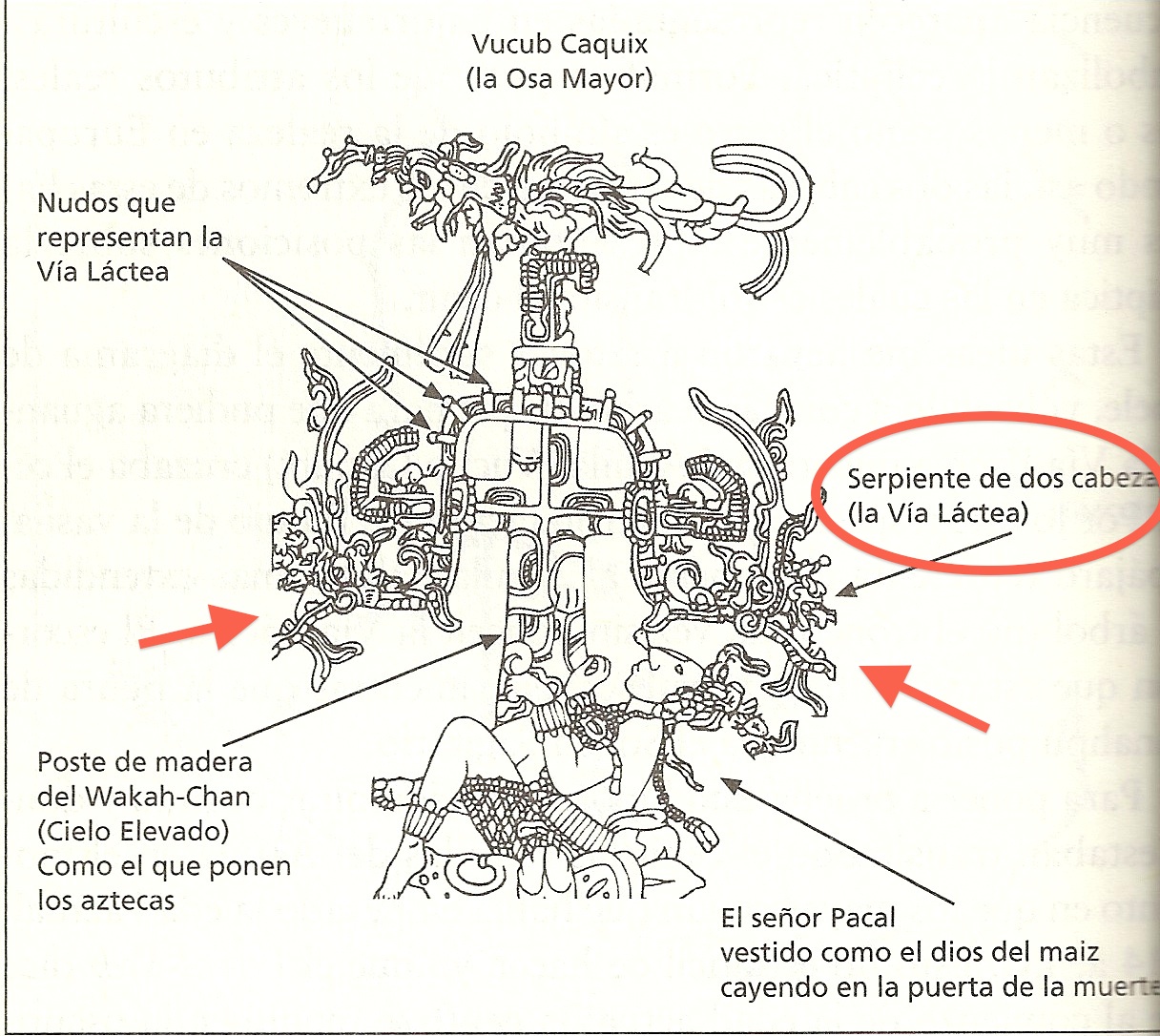

Nearly 4,000 years later this idea of the invisible order would come to define Tamoanchan, the Place of Mist and destiny of souls for the Aztecs. Locally, the place of mist was the center of the axis mundi between “the-sky-and-cave,” which was a “Six place” ritual center (Stuart, et al., 2018: 8). Among the Maya divine kings the place of mist and nature of the king were synonymous, as signified by his holding the ceremonial double-headed serpent bar (lord of the liminal Roads that summoned light and rain, ibid., 9) and sitting on the head of the waterlily-jaguar lord of the underworld or a Pax head that signified the spiritual nature of the World Tree and the king were one. Hieroglyphic inscriptions record names for that royal personage and place such as Lord of the Windy Place, where caves were thought to be the place that wind originated and wind/breath referred to the conjuring cosmic Serpent.

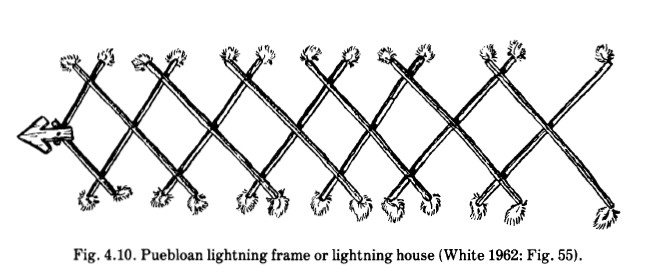

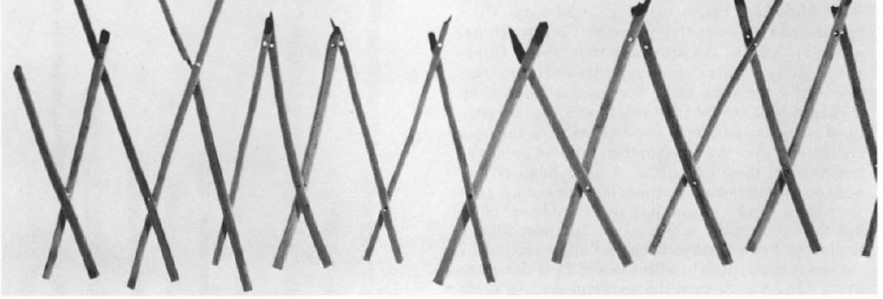

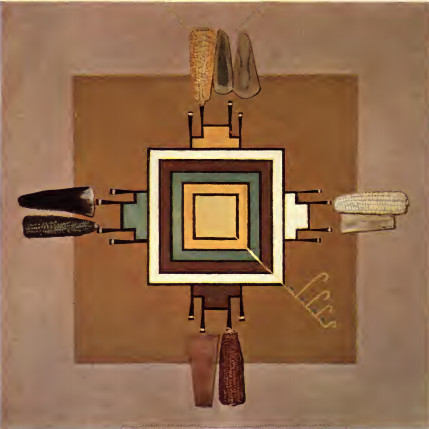

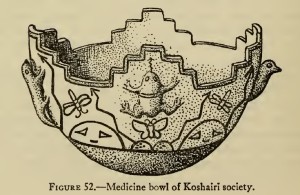

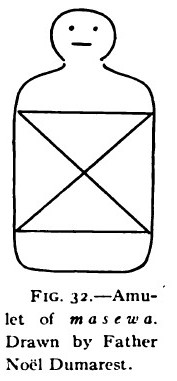

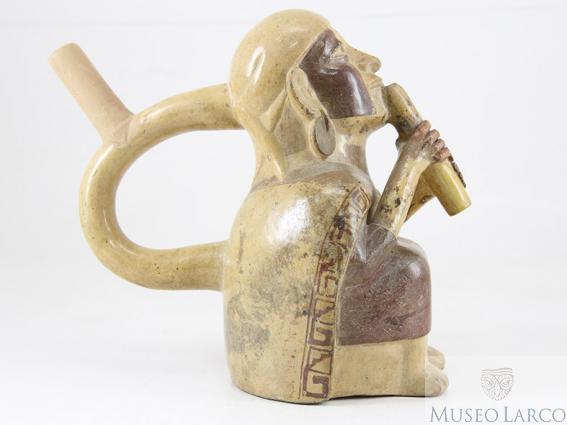

This same idea was preserved by the Zuni in the iconography of their ancestral ceremonial center at Hantlipinkia, which they viewed as their territorial mark (center, bottom panel, Stevenson, 1904). For thousands of years, probably beginning with the shell trade on coastal Ecuador, that idea has been preserved by the high value placed on conch shells (lower left), a natural symbol of how mother sea and father lightning came together in wind-stirred water (foam) to generate life. Apparently the concept of a frothed substance, such as the foam cap of a wave or other types of cascading water or frothed cacao beverages, was an important metaphor for “generative water,” or a substance imbued with the spirit of the wind Serpent, since foam concepts appear in the mythic origins of divine actors and the frothed beverages they consumed from Peru to the American Southwest in the context of Twisted Gourd symbolism. The idea of “bubbly water” as a water scroll was expressed in Maya hieroglyphics by the Water Scroll T579 sign (Rohark, 2019). The water scroll sign, which points to the cosmic Serpent as the breath of life, may be part of a rich lexicon of symbols that included the conch spiral “wind jewel,” which came to be the international archaeological and ethnographic diagnostic sign for the Plumed Serpent cult in Mesoamerica. This further suggests that the agencies of the cosmic water Serpent, already discussed as a tinkuy (meeting, encounter; also spelled tinku) of sun-water (hierophany), was importantly also widely understood as a wind-water tinkuy, with both light/fire and wind forms being vital, life-giving essences resulting from immaterial/material connections [side note: the idea of “stimulated water” (stimulated penis/ejaculate) in the phallic art of the Moche and other Peruvian cultures that developed Twisted Gourd symbolism appears to be related to this lexicon of tinkuys related to the generative aspects of the cosmic Serpent/Milky Way). Based on the centrality of the tinkuy concept, keep in mind that the cosmic Serpent/Milky Way as the birther of the sun (iconic form: Plumed Serpent) and the author of the six sacred directions (Above, Below, cardinal N, W, S, E), the movement of which, stirred by the rotation of the Big Dipper around the North star, created the wind, may have inspired the original idea of the tinkuy in the way that the ecliptic crossed the Milky Way, which corresponded with seasonal changes (Urton, 2013: fig. 62; Green, Green, 2010: fig. 3). These tinkuys, as creative encounters between water and light, appear to have been reiterated in meaningful ways on the earthly plane in all of that ways that sunlight struck moving water to create the sparkling effervescence that generated and sustained life, especially the breath of life. The lightning bolt, notably integral to the stepped mountain design of the Twisted Gourd symbol, was the single most important symbol that represented this “tinkuy” phenomenon as a fundamental generative quality (Staller, Stross, 2013). These concepts of tinkuy as effervescence, radiance and reflection were elaborated by the dot-in-square symbol, a sign of the cosmic centerplace and womb where the sacred directions met and connected the processes of life and death, as represented by shiny metal dot-in-square ornaments attached to royal Moche ritual wear by 400 CE. The symbol served as part of the royal symbolism of divine authority and relationship to the liminal apical ancestors in order to make the human sacrifices that were central to sustaining the world through the sacred bond of reciprocity between human rulers, their semi-divine ancestors, and the sentient powers of nature. This idea is richly narrated in the Hopi’s origin story of the Snake-Antelope society with its dual agencies of sacred song by Antelope priests who empowered the Snake war priests carrying stone clubs (Fewkes, 1894; Stephen, 1929). Using a sanctified club to dispatch an enemy is described later as another form of tinkuy, or the divinely sanctioned encounter in war/bloodshed that is also illustrated by the animate weapons seen in Moche and Maya art.

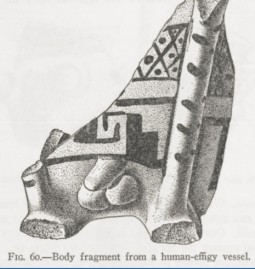

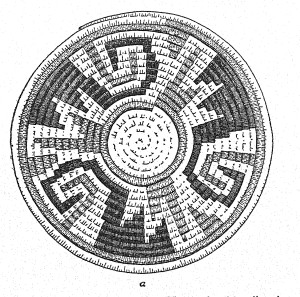

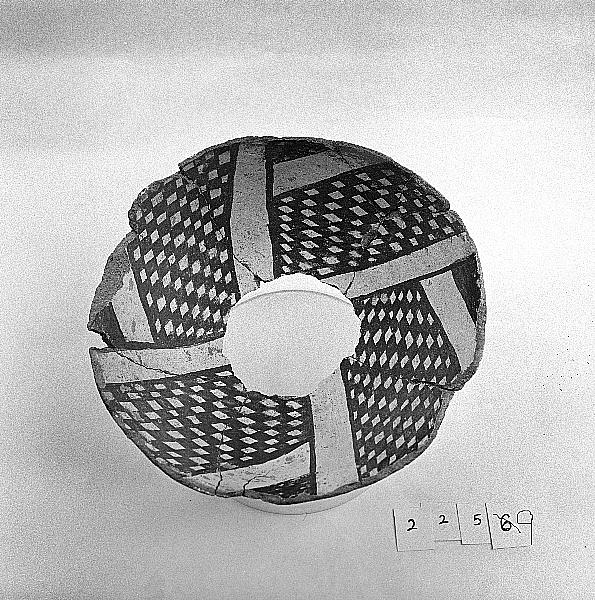

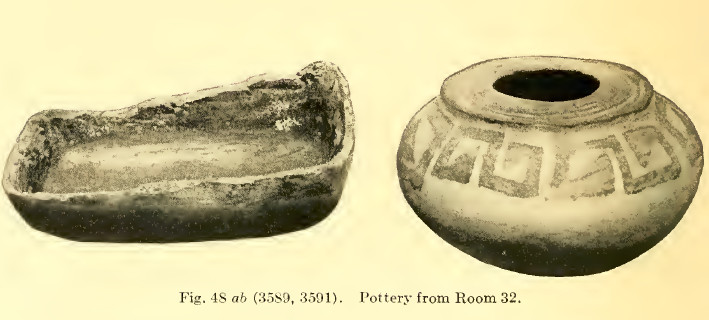

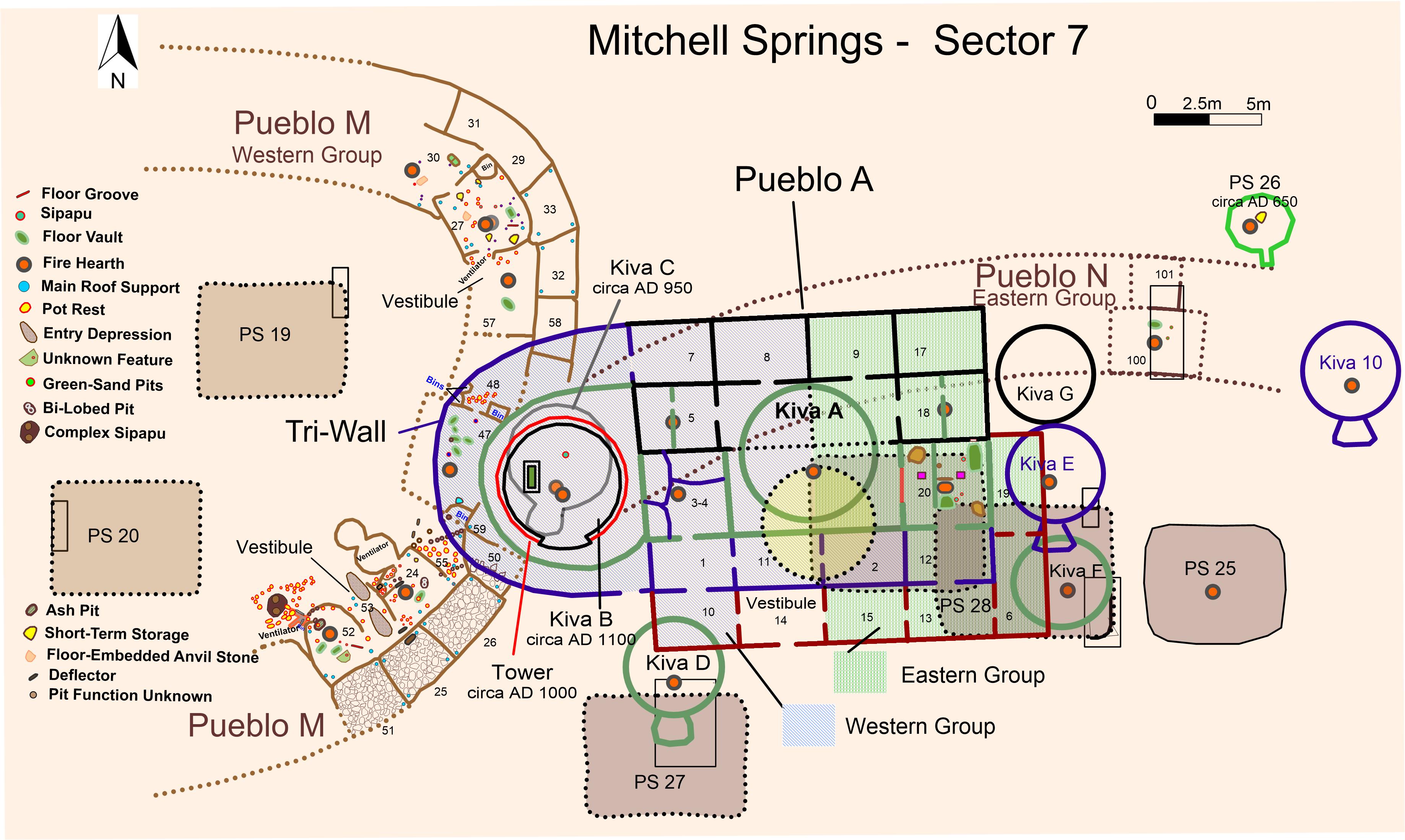

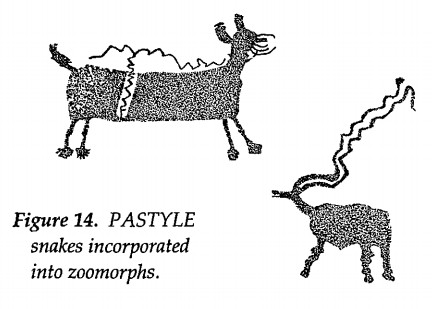

The symbols were a statement of “in the beginning” and ancestry, when light and water, catalyzed by wind, came together to materialize the world as the center of the cosmos in Maya and Puebloan cosmogonies, which was placed like a pearl in an oyster between the Above and Below, which is where the ancestors of the Zuni, Keres, and Hopi, including one with six toes, emerged locally. As indigenous Americans did for thousands of years before them, the Mimbres Mogollon also viewed the author and agency of that creative initiative as the cosmic Serpent which they pictured as a series of interconnected Twisted Gourd symbols arranged in a spiral (top image, tDAR #8014, Style 1 750-950 CE, Wind Mountain site in southwestern New Mexico), the early appearance of which coincided with the Basketmaker-to-Pueblo “Anasazi” transition in the Four Corners region, the construction of Pueblo Bonito, and the hegemony of the Snake-Antelope clan that was based in supernatural ancestry as preserved in the Keres Puebloan origin story. The Bonitians put a similar form of the cosmic Serpent on a bowl they placed along with a conch shell in the burial crypt of their venerated ancestors, room 33 (Pepper, 1920: fig. 69). Clearly, Mogollon elites shared a common identity and/or ancestry with the elite dynasty that occupied Pueblo Bonito for over 300 years. We can therefore confidently presume that 1) the extensive iconography of the snake-mountain sheep deity that was developed by the Mimbres, spread widely by the Jornada Mogollon, and integrated with the cosmic Serpent as the Milky Way will inform the meaning of similar iconography found at Pueblo Bonito and in the Four Corners region (see Part VI–Pueblo Cosmology), and 2) the snake-mountain sheep and snake-antelope images were related through the overarching Horn society and its patron, the two-horned Plumed Serpent called Heshanavaiya as described in the Snake-Antelope legends (Fewkes, 1894), aka Ancient of Directions, author of winds, and denizen of the celestial House of the North from which the axis mundi extended. As will be described in detail in Part VI, the axis mundi constituted three aspects of the Plumed Serpent that connected the celestial above, terrestrial center, and the primordial ocean of the below realms of the cosmos, a scheme that is represented by two interconnected Twisted Gourd symbols as shown in the Mimbres design below.

The horned Plumed Serpent deity as an aspect of the Milky Way at Pueblo Bonito (left, A336145 Smithsonian Digital Archive), called Heshanavaiya by the Hopi descendants of the Anasazi Puebloans, was also venerated by the Mimbres Mogollon (right, Mattocks site, 1000-1150 CE, courtesy of Maxwell Museum/UNM, map).

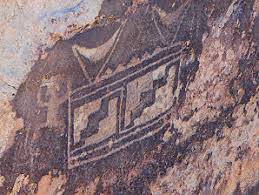

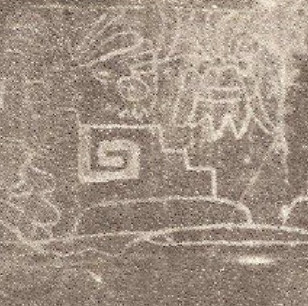

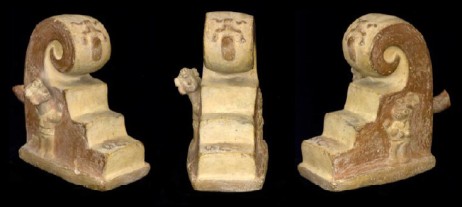

The simplest expression of the catalytic solar (fire/light) : water principle of life (igneous : aquatic paradigm), which seems to be reflected in the fact that Twisted Gourd symbolism developed along coastal South America within the Ring of Fire that constituted the volcanic mountains and lava islands along the Pacific coastline, was represented by interconnected Snake-Mountain/cave Twisted Gourd symbols, as shown above (left) in a Jornada Mogollon petroglyph at the Three Rivers site in central New Mexico, which by extension they associated with horned animals such as the bighorn mountain sheep (right) whose horns projected lightning (shown later in Part VI). The idea of the snake-mountain/cave-lightning/horned animal and ancestral centerplace (Water Mountain) came together in the Mogollon’s concept of the horned Plumed Serpent that is seen in the art of Mexico and again among the Anasazi ancestral Puebloans. The concept of associating the distinctive horned animals (prey species) with the Snake-Mountain/cave-Cloud/lightning ideogram that was the Twisted Gourd symbol rendered in one semantic trope a statement that identified the horned animals as being 1) ancestors wearing bighorn-sheep costumes that were associated with water resources, probably high-elevation river headwaters, and 2) counted among the Stone Ancients that were co-identified with the Chacoans (horn = stalagmite of the ancestral Mountain/cave, the sentient life of horned ancestors preserved in stone as lightning-makers; stalagmites as cave art produced rain, Bassie, 2002: figs. 11-13). References to the cult of the Stone Ancients (snake masters, the Tsamaiya, pronounced Chama-hiya, tcamahia lightning celt) and the historical remnant of the first horned Snake priests are preserved among the Keres-Hopi merger (Stephen, 1929) on Hopi First Mesa (Part VI-Puebloan Cosmology), where the tutelary deity of the Snake-Antelope alliance is Heshanavaiya, the horned Plumed Serpent, and that of the Horn-Flute alliance is Heart of Sky (lightning, Venus as “star god” avatar), the agency of the horned Plumed Serpent (Stephen, 1936a,b). There is a distinction between the celestial, terrestrial, and underworld horned Plumed Serpents that functionally resulted in the axis mundi, a World Tree that was by nature vertically triadic. Puebloan ritual therefore offers a clue as to how the Mesoamerican religion of the Plumed Serpent was integrated locally with high-status clans–three aspects of the cosmic Serpent as a tutelary deity connected the Above (Horn-Flutes), Center (Antelopes, medicine), and Below (Snake-Antelopes) of the Anasazi Puebloan’s universe.

From the beginning of the development of settled agricultural communities, the earliest known religious art of the Americas displayed by the earliest known civilization of the Americas at Caral, Peru, developed as the art of the liminal world of myth where human ancestors, their identity hybridized with the spirits of plants and a trinity of liminal animal lords, would be instructed by the gods to serve as priestly intermediaries between the temporal material world and the eternal liminal realm that gave birth to the visible and regenerated its mortal remains. It was a religion of a social hierarchy that placed those intermediaries at the top of the social pyramid with complete authority over the lives of commoners and their elite relatives with less status. Ritual warfare does not appear to have been a religious-political activity at Caral, nor were there unequivocal signs of human sacrifice, but by no later than 300 CE the Moche’s visual program on pottery and monumental architecture indicates that ritual warfare was a key feature of dynastic political life and human sacrifice was practiced. The same was found among the Maya, who acquired Twisted Gourd symbolism by no later than 300-150 BCE, and by the Classic period similar iconography related to dynastic ritual warfare and human sacrifice was evident. Currently Twisted Gourd symbolism has been retained among a handful of Keres, Zuni, and Hopi artists among the Puebloans nee Anasazi of the northern American Southwest, but although all Puebloans share a common indigenous religion, today ownership of the Twisted Gourd symbol, at most, may signify a high status clan lineage that retains a cultural memory of the “Ancient ones” of Chaco Canyon, but that clan retains none of the authority of the dynasty that once occupied Pueblo Bonito as the center of the Chaco sphere of regional influence. There, artists writing in a symbolic language about the cosmic power of the centerplace and its occupants had the final word on regional communications, and the living word of the elite symbols impressed into rock or clay wasn’t for sale to tourists. Assuming that the rest of the symbol set was available to provide cosmogonic context, for all intents and purposes the Twisted Gourd symbol and its associated symbol set were equivalent to a European royal coat of arms from an ancient “House of…” lineage throughout South America, Central America, and Mexico (see The Serpent Motive in the Ancient Art of Central America and Mexico, Gordon, 1905).

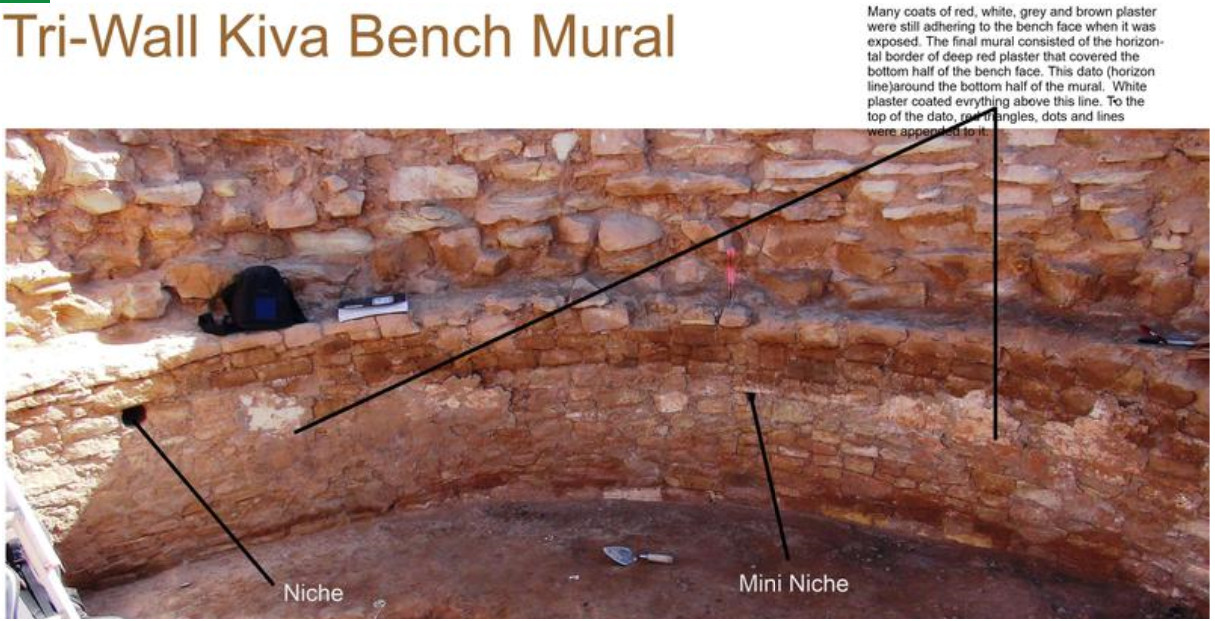

Twisted Gourd symbolism has endured for over 5,000 years as the symbolic language of America’s indigenous cosmovision. The Twisted Gourd symbol is the earliest known example of design as agency on durable surfaces–gourds, stone monuments, ceramics– that would come to represent a religious-political cosmovision of social theocracy as an ideology of legitimate governance of the early agricultural communities. It saw the Milky Way as a cosmic Serpent, functionally as a river of life, with both a radiant and a hidden nature that materialized as rain clouds and lightning to unify the triadic realms and sustain its jewel of a center, the navel of the earth. This cosmovision is currently preserved as the life-way of the descendants of the Anasazi Puebloans who lived in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, and the surrounding Four Corners region, where one of the earliest complex societies in North America will surely be ranked among the most capable of Mesoamerica’s high-status architects and masons, work whose patron was the deified cosmic Serpent as a complementary Maker (Designer)-Modeler (Doer) unity, which was also the Maya’s name for the cosmic Serpent as the creative agency embodied in Kukulcan, the quetzal-bird–Serpent (Tedlock, 1996: 63).

The Designer-Doer dyad as the name and agency of the sovereign source of knowledge and sustainer of life–ultimately the water : fire Serpent and Sun unity that was embodied in a Sun priest called the Tiamunyi– was reflected in the sovereign Plumed Serpent’s Heart of Sky-Heart of Earth poetic construct, which was the axis mundi that bloomed as the Tree of Life. The same construct was also reflected in the deity : human dyad of hereditary rulership as the form of governance mediated by the divine ancestors of kings, or by whatever title the Doer at the peak of the social pyramid, literally represented by the Twisted Gourd symbol–the stepped abode of the ancestral Snake-Mountain/cave-Cloud ideogram–was known. The sacred name of the cosmic Plumed Serpent, whose antecedent was South America’s feathered amaru (“big snake”), was one of the ethnographic cultural markers that tracked with the archaeological marker of the Twisted Gourd symbol as the Maker-Doer cosmovision– the Sky-Earth construct that connected cosmic agency with humanity in the sacred precinct at the heart of the ancestral Mountain/cave–moved north out of South America in the context of Twisted Gourd symbolism. Furthermore, the Maker-Doer construct as an invisible spirit-visible actor dualism that notably works through a hereditary lineage and its descendants appears to be a feature of other ancient indigenous religious-political traditions. For example, the creator deity of the Hebrew scriptures, where the spirit is ‘the vital force of the deity,’ that engendered an authoritative human lineage through Abraham. Comparatively, the difference between the indigenous spirit of the Americas and that of the Middle East and Levant is that in the Americas the omnipresent vital spirit was understood through the metaphor of a zoomorphic cosmic Serpent (Milky Way, light-struck water, plumed Serpent) that created the first Corn priest-kings, while in the Middle East the vital spirit of the creator deity that manifested in water, fire, and wind and created the first pair of humans not from corn but from clay was understood as an anthropomorphic being. Comparing the origin story in Genesis to that of the Maya and the ancestral Zuni Puebloans, the supreme creator deity with its vital force in all three cases lies outside of time and nature as thought (sentience), and therefore could manifest in all aspects of the created order and as the source of prophecy through priests.

The Designer-Doer name of the supreme spiritual agency in the clouds of the Milky Way is still preserved among the Zuni Puebloans as Awon-a-wilona (Stevenson, 1904:88; Parsons, 1920:97 fn 2; Cushing, 1894:9), the Thinking cosmic Serpent as Sky Father, the Designer of the roads of life that extended from the axis mundi in the context of Twisted Gourd symbolism– the mythological narrative of the cosmic Centerpoint associated with royal hereditary rulership (divine ancestry). Among the Hopi Puebloans the Ancient of the Six Points as the axis mundi and source of warm winds (thought, speech, song, spirit, breath of life) was called Heshanavaiya/Four Winds, the horned Plumed Serpent and life-giver (Fewkes, 1894; Stevenson, 1904; Stirling, 1942). Among the Acoma Keres Puebloans the pan-Amerindian cosmogonic construct that from “four skies up” formed the axis mundi and generated the Corn mother in the heart of the earth was Tsichtinako (Stirling, 1942: 1:2, 25). While the ethnic name and narrative details of the Designer-Doer pair differed among the Puebloans, the most legendary being the Tsamaiya (tcamahia), a mytho-historical warrior medicine priest and namesake of Heshanavaiya, the father of the Snake-Antelopes, the semantics and function of the divine agency as the designer of the sacred roads, mytho-historical clan ancient as the ancestral doer in ritual, and cosmovision of an integrated universe where the radiant divine agency (unified sun-water nature of the cosmic Serpent) and its human Speaker remained distinct.

The fact that, in the context of Twisted Gourd symbolism, the Maya and the ancestral Puebloans shared the vertically triadic and horizontally quartered cosmos, the same concept for the six points of the sacred roads (directions), the same concept for a celestial House of the North from which extended the axis mundi, the same concept for the Maker-Doer creator that was integrally connected with the ancestry of an elite social stratum, the same Heart of Sky-Heart of Earth axis, the same concept for the apotheosis of a dead ruler who returned to the celestial House of the North as a revered ancestor, and the same concept of a cosmic circulatory system of “dew” and living breath that were aspects of the Plumed Serpent clearly indicate that the ideology of rulership that was based on the sacred directions through which “dew” as a blessed substance flowed was in fact the cosmovision of the centerplace–the Snake-Mountain/cave-Cloud/lightning narrative– that was represented by the Twisted Gourd symbol. The documentary evidence that reconstructed the axis mundi of the ancestral Puebloans in this monograph as extending from celestial North parallels the architectural evidence from Pueblo Bonito that the “Ancients” also conceived of the axis mundi as extending from celestial North (Ashmore, 2008: 179, 184-186). With that being the case and in the context of Twisted Gourd symbolism we now have a clear picture of the Chacoan’s religious-political cosmovision and their basis of social hierarchy.

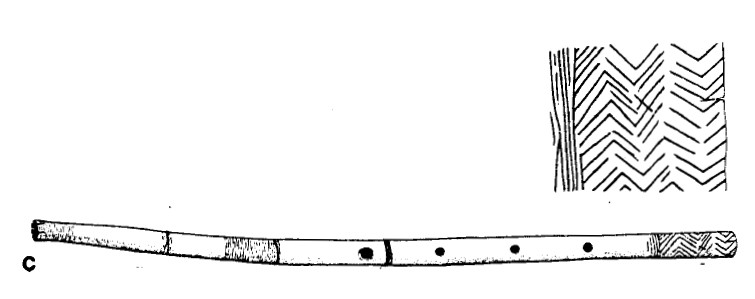

Moreover, it is increasingly clear that the ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi) of the northern American Southwest c. 750 CE shared the same or a very similar worldview of the first Mayans c. 300 BCE to 200 CE. The zoomorphic centerpiece of that worldview was the cosmic Serpent (Milky Way), a metaphor for the unity of light and water (hence, life and fecundity), a far-reaching theme that was encoded by Twisted Gourd symbolism and its ideologhy of legitimate divine rulership. In the American Southwest, the geographic distribution of Twisted Gourd symbolism happens to overlay the distribution of rock art of the ancient, often phallic and “plumed” (sun rays) Flute Player (Malotki, 2000: fig. 1), which may indicate a further association between phallicism (manliness, fertility), fecundity, the sun, and the breath of life that associates flute music with the cosmic Serpent, with Twisted Gourd symbolism, an ideological grouping also seen among the Maya at ceremonial centers displaying Twisted Gourd symbolism (Amrhein, 2003; Vega, 2015). These themes and memes all appear to be part of a symbolic lexicon that “says” something like “life and its continuity” that was associated with ceremonial centerplaces that were the seats of divine rulers.

The unifying theme of the cosmic Serpent therefore ties together 1) the light-water unity as the sacred basis of life; 2) the cosmos as represented in a divine human body residing at a cosmic ceremonial centerplace; 3) and the conception of the breath of life that was associated with the Plumed Serpent as represented by warm wind, music, and fertility, which was indexical for an indigenous worldview observed in archaeology and ethnography as far north as the Anasazi in the Chacoan sphere of influence and as far south as the earliest Maya in Mesoamerica (Rice, 2007). Among the Anasazi ancestral Puebloans, this pan-Amerindian ideation, with an origin in Peru as represented in cosmogonic myth, art, and ritual, was culturally concretized in a Snake-Antelope zoomorph called Heshanavaiya (-aiya, Keres Puebloan: gods, life bringers, as related to naiya, the Corn Mother known as Iatiku; Taube, 2000), aka the four-horned Plumed Serpent as the spiritual father of the ancestral Puebloan’s Snake-Antelope cult, who was the author of the sacred directions, birther of the sun, and source of warm winds and fecundity.

The human rulers who embodied this entire cosmological and cosmogonic drama of creation and rulership in the Keresan “language of the underworld” were male twins called the Tiamunyi (sun priest) and Tsamaiya (war priest), who in turn embodied Mesoamerica’s mythical Hero Twins, the sons of the Plumed Serpent/sun. The mythological role of the youthful Hero Twins in Maya (Tedlock, 1996) and Puebloan cultures provided a dualistic Above/Below model of leadership that unified heaven and earth with these two human actors. As expressed in the Zuni creation myth, the Hero War Twins, as the sons of the Plumed Serpent/sun and the Earth Mother, were created to rule with divine authority over the unified sky/earth/underworld realm as the sine qua non model of leadership: “And of men and all creatures he gave them the fathership and dominion, also as a man gives over the control of his work to the management of his hands” (Cushing, 1896: 382). For emphasis, it must be pointed out that this dynamic myth-based construct not only provided for the unity between sky, earth and underworld and human rulership, it also provided the space-time bridge between the first days of creation and present time, e.g., a myth-history for a dynastic family.

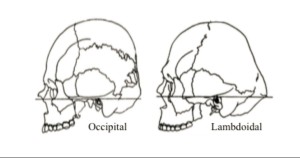

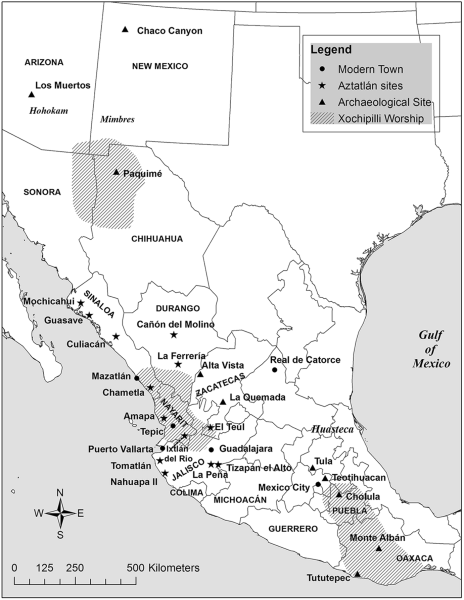

While the weight of evidence strongly suggested that the Maya and Pueblo cultures were linked ideologically through a shared worldview centered around the Plumed Serpent, symbolic lexicon, and distinct visual conventions in design and clay forms (especially the cylindrical vase associated with a cacao beverage; see clay artifacts), the strategic cultural role played by the cosmic Hero War Twins who ruled over the centerplace (earth) through a human dynasty confirmed it. In the American Southwest, this worldview as evidenced by Twisted Gourd symbolism was shared by the ancestral Puebloans, Mogollon, and the Hohokam people along trade routes that lead directly into Mexico (Carot, Hers, 2006; 2011; 2016). The common physical adaptation that associates with the spread of Twisted Gourd symbolism from Peru through the Maya and to the Pueblo culture of the American Southwest is the lambdoid cranial modification. The “road of the Serpent” (van Akkeren, 2012b) that linked ceremonial centers also appears to have been the road of elite traders who carried emblems of the authority of the Plumed Serpent cult, such as tropical feathers, macaw (a sun/fire symbol), and cacao, to Mesoamerican dynasties (Zuyua hypothesis: Lopez Austin, Lopez Lujan, 2000; Zuyua, Place of the Gourd: van Akkeren, 2006) and into the American Southwest along trade routes marked by the Flute Player icon and quadripartite symbol that was part of the Twisted Gourd symbol set (Carot, Hers, 2006; Carot, Hers, 2011).

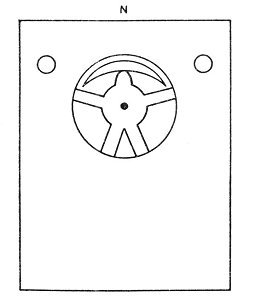

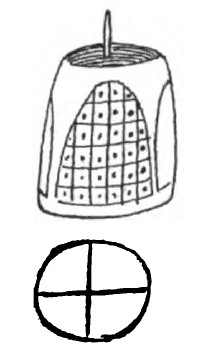

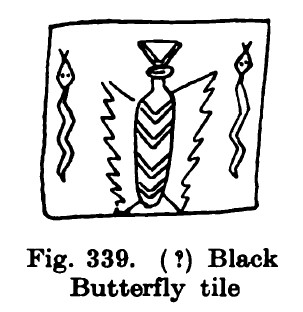

Hohokam Flute Player c. 800 CE (Wallace, 2014: fig.11.5). Note the association between the quadripartite symbol of the Plumed Serpent (author of the space-time ordering principle represented by the sacred directions and annual soltitial paths of the sun), fertility, and the plumed Flute Player, a priest of the fire-snake, or the unity of light and water. The equal-arm quad symbol is integral to understanding the Twisted Gourd symbol and its relationship to the fertility that sustained the life-death-regeneration cycle of life. Like the traditional Christian cross, the quad cross symbolized an utter conviction of the unity of heaven and earth, and wherever the Twisted Gourd symbol was displayed, it signified a place and authoritative person(s) where that unity occurred through rituals that created a sacred space of reciprocity considered to be the centerplace of the axis mundi that passed through the womb-cave of a sacred mountain to join heaven, earth, and the underworld.

Lightning, Clouds, and Thunder Storms: The Meaning of the Twisted Gourd Symbol as an Archetypal Snake–Mountain/cave–Cloud/lightning Topocosm of the Relationship (Centerplace Connections) between Supernatural Ancestors, Eternity (Liminal Space Outside of Time), the Temporal World, and Rulership

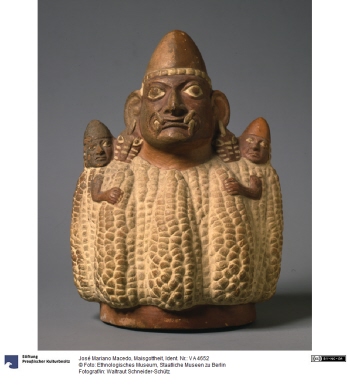

Reading the symbolic narratives preserved on durable artifacts of pre-literate ancient societies is like reading their books. The key to unlocking those narratives was the decoding of Twisted Gourd symbolism and the cosmovision of a triadic world it represented. Twisted Gourd symbolism was an art of the liminal dimension of reality, where the timeless space of living-dead ancestors and creator gods co-existed side-by-side with the material sun-lit world, the realm of time. The liminal represented the primordial ancestry of elites who were entitled to rule because they were direct descendants of the Makers of the triadic material world of the first humans when the world was new. The Makers were represented by a trinity of animal lords, each a predator and dominant over its own kind as conduits of spirit. These were the archetypal Bird (sky), Feline (terrestrial centerplace), and cosmic bicephalic Serpent (underworld: primordial ocean as the lower aspect of the Milky Way-sky). Hence, the water Serpent as the zenith, center, and nadir of the axis mundi and the basis of mythical hybrid animal spirits that connected the celestial Above with the Below and the terrestrial east with the west even as they linked the inner nature of a king with their creation.

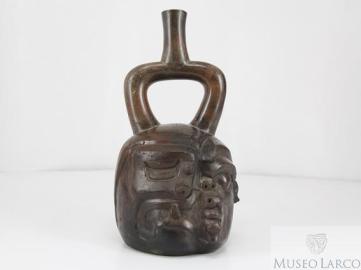

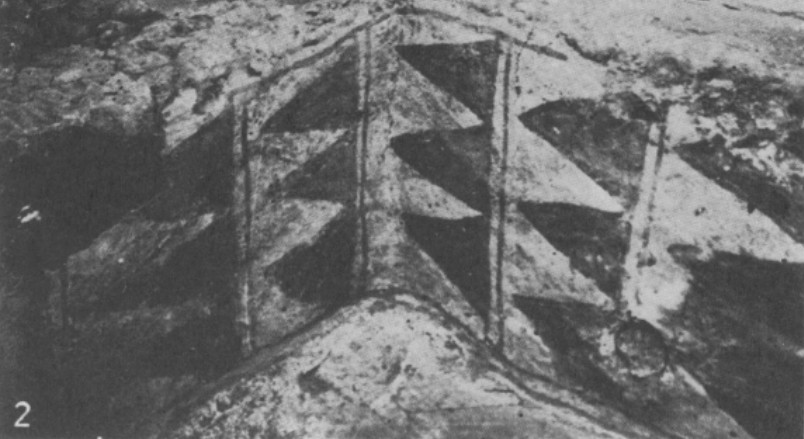

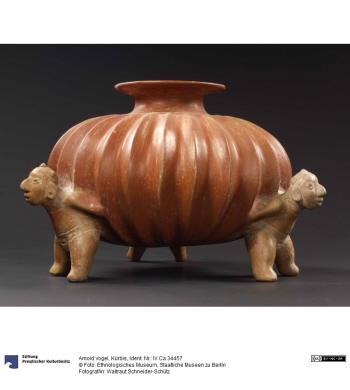

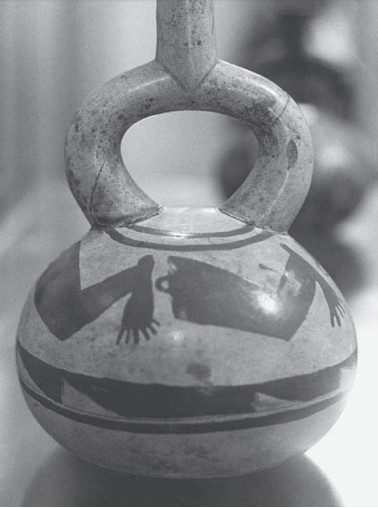

In the image above, on the edge of the gourd to the right of the Staff god is the Twisted Gourd symbol (Nahuatl: xicalcoliuhqui), which is the oldest symbol in the Americas representing the cosmic Serpent as a Serpent-Mountain/cave-Cloud ideogram, the iconic metaphor for the Sustenance Mountain centerplace of the cosmos upon which an ideology of rulership evolved. An especially revealing ceramic example of the meaning attached to the conflation of the Mountain/cave with the overhead Cloud, and the Snake with both Mountain/cave and Cloud, to visually extend a profound insight is Moche vessel ML012790 from an elite tomb c. 100 CE. That Peruvian example shows the dualism of dark and light embodied in interconnected Twisted Gourd symbols, wherein the Cloud of the visible world (dark triangle, the Cloud-Serpent as water) is at once the misty interior of the Mountain/cave in the mirrored Twisted Gourd of the complementary pair, the place of origin from which Sustenance and the helpful Ancestors arose. The juxtaposition of the S-shaped serpent bar (Milky Way river of life, in this case attached to a lunar symbol) with the Twisted Gourd symbol on ML012790--both narratives of royal power based on supernatural ancestry– is also key to the association of mytho-cosmological ideas that created a viable worldview that has persisted among indigenous Americans to this day (more: Maya Connection). Lightning was the singularly important trait that characterized divinity and social elites. As such the ideogram further represented a lightning snake (zig-zag light area) and seat of ancestral rulership–note the light and dark materializations of the cosmic Serpent that had visible (over the sacred mountain) and invisible (within and under the sacred Mountain/cave) forms– that signified the Snake as patron of rulers could unite the sky with the earth and its inner world to provide sustenance to the community with the help of the living-dead ancestors.This represented the governing paradigm that for 3.500 years prior to the Spanish conquest guided the cultural development of the early agricultural theocracies in the New World. It would become the defining theme of the earliest known organized religion of the Americas that shaped architecture, ceramics, and the visual program of rulership from South America to the American Southwest. Twisted Gourd symbolism in South America first developed during the era when maize cultivation at Norte Chico in the late Archaic c. 3000-1800 BCE was widespread as a basic staple of the diet (Hass, et al., 2013), which may suggest an early association, but Twisted Gourd symbolism was without doubt associated with the rise of the first complex societies, and at Norte Chico it was cotton as a trade commodity that appears to have been a major driver of cultural development

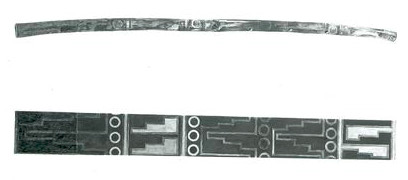

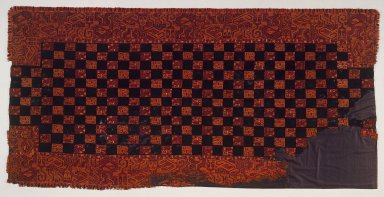

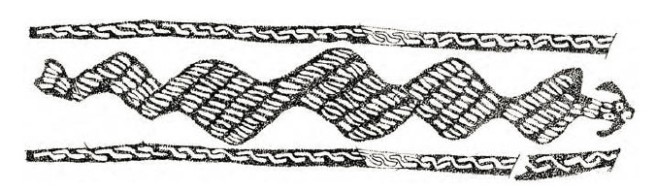

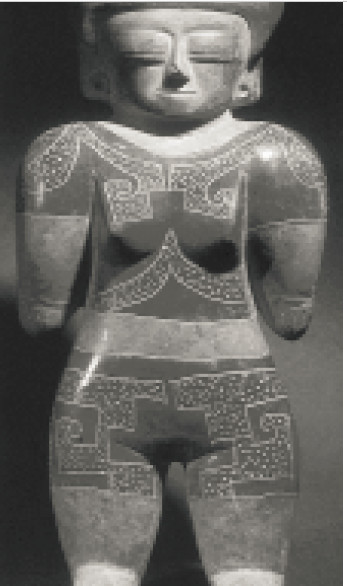

Left: Double-headed S, the bicephalic cosmic Serpent on a textile band encircling the mortuary bundle of the Lady of Cao, a Moche ruler and priestess c. 300-400 CE. The body of the snake displayed the black-and-white bar pattern that represented a sideview of the checkerboard Milky Way-sky pattern as the cosmic Serpent (see ML012866). The black-and-white bar pattern as the Milky Way river of life that was synonymous with the cosmic Serpent–the Horned Serpent or Quetzalcoatl in Mesoamerica– persisted everywhere Twisted Gourd symbolism took root, including among the Mogollon and Anasazi Puebloans. The stepped fret of the Twisted Gourd symbol, itself an archetype of the “place of mist” of social elites that signified their kinship with creator deities and the archetypal place of origin, was the cosmic Serpent (the Milky Way), which was integrally associated with the ancestral Mountain/cave abode of anthropomorphic clan ancients, such as the Moche’s Aia Paec, a snake-jaguar Mountain Lord and the Lady of Cao’s tutelary deity, who wore the Milky Way as his checkered bicephalic snake belt (see the “misty” nature of the Sacrifice/Presentation ceremony in the context of the Milky Way-sky bicephalic serpent and Twisted Gourd symbolism).

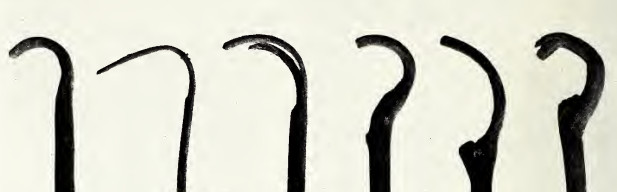

Reflecting a 3500-year period of development of Twisted Gourd symbolism associated with rulership in northern Peru and divine royal breath, (left to right) ML100604, ML100749, and ML101454 are examples of silver nose rings that were buried with Chimu elites during the Imperial era 1300-1532 CE prior to the successive Inca and Spanish conquests. Compared to the design of the Chico Norte artifact of 2250 BCE shown above, the “bare bones” symbolism of the simplest nose ring on the right indicates that the central design of white snake-lightning connecting the dark stepped forms that conflated the Snake-Mountain/cave with Cloud (a sky-earth construct or “connection” between the material and liminal realms) was the supernatural quality associated with the elite authority of a royal family extending from a deified ancestor that occupied the liminal realm of the archetypal Snake-Mountain/cave (central image). Conjoined Twisted Gourd symbols at once inferred the symbolic equivalence of the ancestral Mountain/cave, stepped pyramidal temples, and the chakana symbol. That equivalence was in turn embodied in the supernatural powers of a royal lineage that had direct access to the liminal realm of the unified Above, Middle, and Below planes of existence. In short, this one symbolic collage explained the who, what, when, where and why of royal authority as the truth of an established cosmovision. Worn as a nose ring, this symbolic collage associated the breath and spoken word of a human authority figure who personified those supernatural connections with the breath and spoken word of a deified ancestor and god. A question that remains to be answered is were these high-value artifacts, which were possessed only by elites, considered to be “agentive media” where symbolic representation created a desired reality through magic? Or, were symbol-laden artifacts politicized representations of a widely understood cosmological aspect of rulership that through ownership alone (“identity politics” of status) communicated to the gods and the public those who served at the peak of the social pyramid

As will be seen among the Maya and ancestral Puebloans as well, dynastic lineages were intimately connected with the mythology of the Milky Way Serpent from birth to a state of the living-dead as revered ancestors. The hereditary lineages that occupied a place of mist and served at the top of a regional social pyramid were “functionally divine while living and were elevated to ontologically divine status upon becoming apotheosized ancestors after death. As apotheosized ancestors, they took their place in the pliable local pantheon which further reinforced the unique identity of each site” (Wright, 2011: ix). Among the ancestral Keres ancestral Puebloans that “pliable local pantheon” was referred to as kopishtaiya, the lightning-, thunder-, cloud- and rainbow-makers. Over time, several lineages linked by kinship could claim divine ancestry of the corn life-way and seek to become the overarching leader, but “the real fact of royal divinity was not so important as the relations which the king formed with other gods and men, and the contexts in which he was able to assert his divinity” (Houston, Stuart, 1996: 289, citing Burghart, 1987). Moreover, the mortal divine ruler was not entirely like-in-kind with a true cosmic agency like the water and fire gods although he was related to those agencies. In that sense divine rulership was in fact local, which may account for the tendency of the Moche and Maya rulers of small city-states to form alliances and dominate their neighbors as a show of supernatural approval .

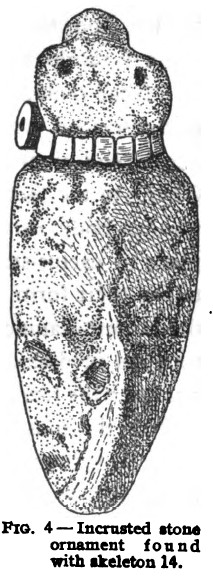

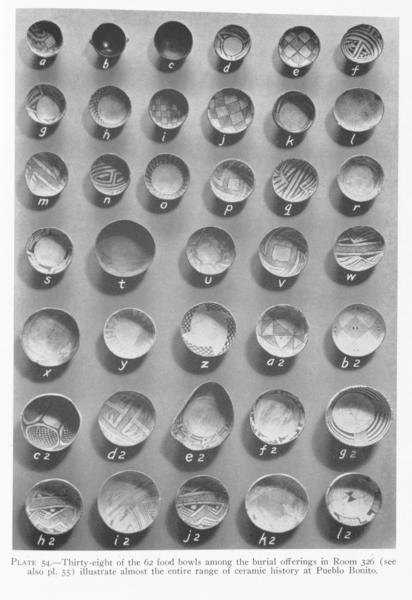

Although we don’t know with certainty the rank and title of the two male burials in room 33 at Pueblo Bonito, the fact of the location of their earthly remains, its ceremonial context of feasting and Twisted Gourd symbolism, and the amount of turquoise buried with them to designate the blue-green heart of the cosmic navel indicates that these men were revered Bonitian ancestors that made a pilgrimage to Pueblo Bonito worthwhile and established the status of their descendants. Out of the corpus of ancestral Puebloan ethnography there was only one leader who perfectly the fundamentals of Maya divine kingship and the artifacts found in room 33, and that was the Acoma Keres Tiamunyi with his Tsamaiya (tcamahia) Twin, a mother-father actor that will be discussed throughout this report.

Across all pan-Amerindian monumental and portable art, the snake (all directions, centerplace) and the jaguar (centerplace, cosmic navel) were always connected in the archetypal Mountain//cave centerplace as water and sun/fire signs, respectively, in the context of Twisted Gourd symbolism and the trinity of animal lords. These were references to 1) divinity and the nature of the cosmos, 2) the intermediary clan ancients (anthropomorphic revered ancestors who had acquired the nature of the god, like the Moche’s Aia Paec), and 3) the nature of rulers and rulership. The trinity of archetypal animal lords correlated with the Above, terrestrial Center, and Below realms of the cosmos and were associated with rulership (k’ul ahaw, holy lord) as way (pl. wayob), spiritual animal companions. The double-headed Serpent scroll (the Cloud-Serpent), especially in the form of a royal scepter, became the dynastic signature for that cosmological complex that was based on “the place of mist,” a metaphor for the pervasive spiritual nature of the cosmic Serpent as existing outside of time, the Serpent’s materialization as the Milky Way-sky river of life, and the archetypal Snake-Mountain/cave-Cloud/lightning narrative of interconnected Twisted Gourd symbols (mirrored liminal/material realms joined by a portal). The interconnected Twisted Gourd symbols, as in the original example from Norte Chico’s Caral culture 2250 BCE, inferred an axial connection between the Above and Below as well as east to west as mediated at the Centerpoint by the jaguar-snake Mountain/cave lord.

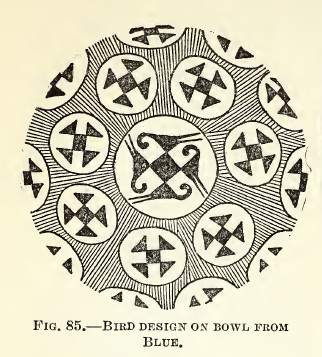

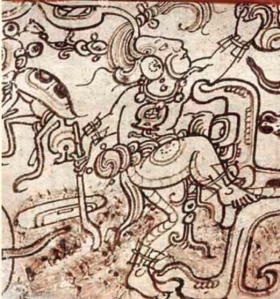

![]() While “place of mist” appears to be the overarching pan-Amerindian metaphor for the ancestral Snake-Mountain/cave-Cloud archetype, the occurrence of Twisted Gourd symbolism in a culture was also associated with the place names “Place of Herons/Cranes” and “Place of Reeds” and notable cormorant, crane, or heron iconography as other likely metaphors for the archetypal place of primordial beginnings with which rulership was associated (see ML010478; K4687, and Maya example to the left; also Gallina Nogales Cliffhouse), but an investigation of the waterbirds in terms of identifying a ruling hereditary lineage, although a trope common to Moche, Maya, and ancestral Puebloan elites, lies beyond the scope of the current investigation. However, I point it out as an area of study that likely will reward an inquiry (see Mimbres Mogollon 700-1000 CE tDAR #8014 for an approach to visual conventions related to the trinity of animal lords as ancestral nahuals (wayob) of elite hereditary lineages).

While “place of mist” appears to be the overarching pan-Amerindian metaphor for the ancestral Snake-Mountain/cave-Cloud archetype, the occurrence of Twisted Gourd symbolism in a culture was also associated with the place names “Place of Herons/Cranes” and “Place of Reeds” and notable cormorant, crane, or heron iconography as other likely metaphors for the archetypal place of primordial beginnings with which rulership was associated (see ML010478; K4687, and Maya example to the left; also Gallina Nogales Cliffhouse), but an investigation of the waterbirds in terms of identifying a ruling hereditary lineage, although a trope common to Moche, Maya, and ancestral Puebloan elites, lies beyond the scope of the current investigation. However, I point it out as an area of study that likely will reward an inquiry (see Mimbres Mogollon 700-1000 CE tDAR #8014 for an approach to visual conventions related to the trinity of animal lords as ancestral nahuals (wayob) of elite hereditary lineages).

This integrated, pan-Amerindian cosmological scheme that equated the nature of the cosmos with the nature of a dynastic head via a unitive fire : water principle is the antecedent to what Lopez Austin detected in his Mesoamerican studies (1997, 2000) as the igneous : aquatic paradigm, a living-stone/fire : water construct that described the archetypal essence of the materialized Mountain/cave centerplace in its primordial context within the “place of mist,” the sky/ocean Otherworld that surrounded and perfused it (liminal space); refer to the discussion of the igneous : aquatic paradigm in the celestial House of the North sidebar. That surrounding and perfusing constituted the sacred directions, the “roads” of the Plumed Serpent upon which gods and ritualists traveled to meet in the rainbow centerplace (see chakana and kan-k’in symbols). What the ancestral Puebloans contributed to our knowledge of that paradigm was an archaeological site and substantive ethnographic material that described a place of mist (Chi-pia centers associated with the mythological Puma and the Great God– the wind god aspect of the Plumed Serpent) and how it functioned as a place of high-status priestly initiations and transit point of mythological clan ancients, the ancestors of ritualists, between liminal and material realms. In the Mesoamerican vernacular, a Chi-pia center would have been called a Three Stone Place of a Maya king, the centerpoint of the cosmos defined by its cosmic hearth, which pointed to the foundation of the material world in space as the placing of the Jaguar Stone throne, the Snake Stone throne, and Itzamna’s Waterlily Stone throne that bound the Snake and Jaguar together, which was explicitly associated with the Twisted Gourd symbol (K623), as was the supreme god of king’s celestial throne (K1183). If we take the name and design of the Twisted Gourd symbol literally (xicalcoliuhqui), we would have “twisted” (curving or stepped snake frets, vines, which referred to the twisting lightning and whirling wind forms of the cosmic Serpent) plus a squash gourd, a “water house” with seeds in the interior (xicalco, in a calabash), literally the Snake-Mountain/cave of Sustenance. The xical, the netted gourd water carrier and ceremonial gourd cup used in libation rituals, conveyed that central vision of the birth, death, and regeneration cycle.. Twisted Gourd symbolism narrated a story of a place, an agency, and the role of hereditary lineages–both human and divine– in coming together to ensure the welfare of the human race.

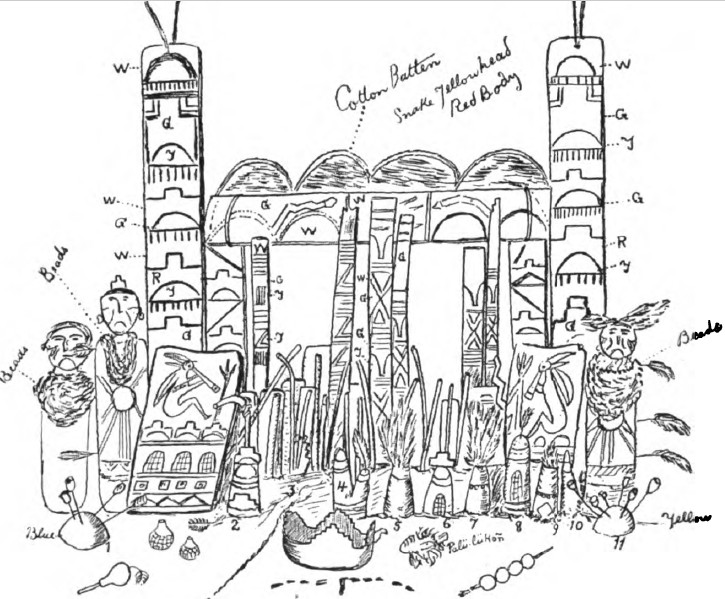

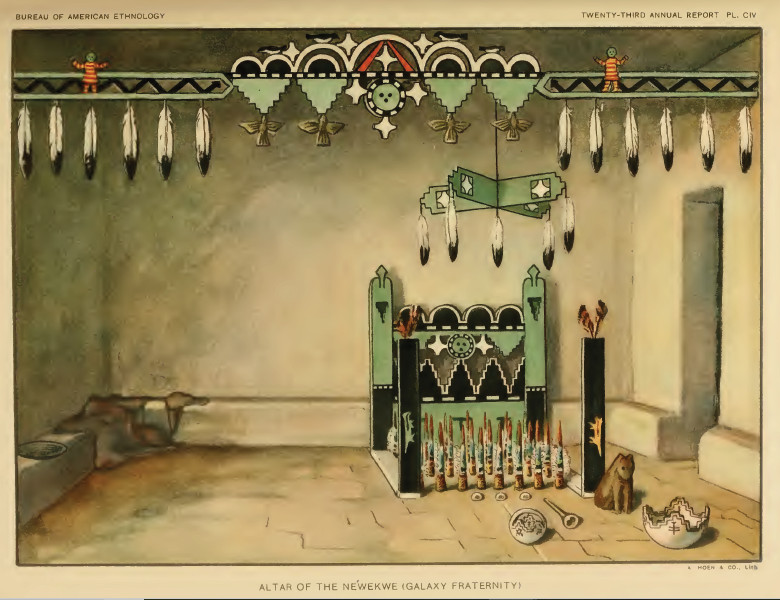

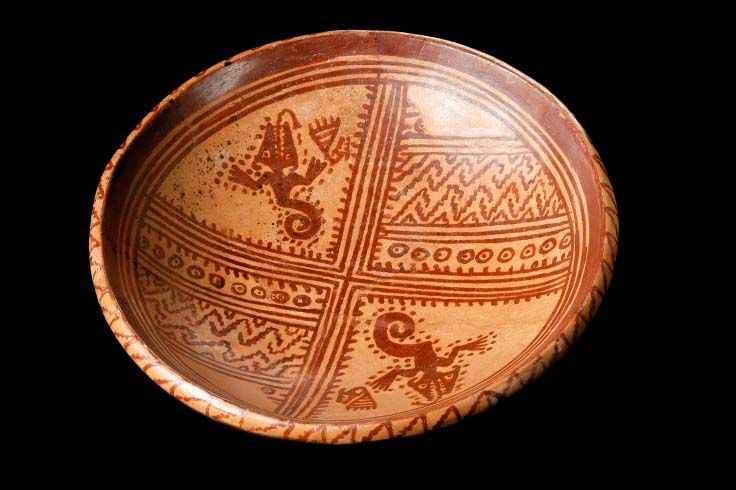

How was the concept of primordial, everywhere-present Mist as the nature of the cosmic Serpent and Cloud-state of the Ancestors materialized in a visual program? If anyone has ever hiked to the headwaters of a river, it is obvious that a river originates from a cave or its analogue (seepage from cracked boulders, etc.) and as mountain run-off becomes splashing waterfalls, lakes and springs at lower elevations, e.g., the concept of a watershed and the mountain as a water house. Through observation, and cast in enduring archetypal terms, there was a pan-Amerindian belief that rivers, clouds, and wind emanated from a people’s sacred cave, their ancestral centerplace, which was encoded in the Snake-Mountain/cave-Cloud/lightning narrative of the (stepped fret, Snake + stepped triangle, Mountain/cave-Cloud) Twisted Gourd symbol. Based on that foundational understanding, and the fact that the cosmic Serpent of the Milky Way-sky embodied the spirit of water, images that included 1) an array of rain drops/mist underneath the Milky Way arch of the cosmic Serpent with ancestors sitting on clouds nearby (see ML004112; Moche coca ceremony, section 3); 2) a mythological Mountain Sheep-like creature next to a shaman’s ceremonial pouch containing hallucinogenic tobacco and surrounded by a spray-painted sky dome (interior of a bowl, where the paint had been consecrated by the water and breath of the Serpent and aerosolized in the saliva of a priest, Fewkes, 1898: fig. 264 and pl. CXXX); an explicit visual narrative such as an ancestral deity related to the concept of the trinity of animal lords shown in the context of the checkerboard bicephalic serpent arch (Milky Way-sky, ML012866; compare to the checkerboard Milky Way-sky band with a Cloud house on the Zuni’s Galaxy altar and note the continuity over time and distance of the checkerboard pattern’s association with the Milky Way-sky as the essence of the bicephalic cosmic Serpent, Stevenson, 1904: pl CIV); drawing a species associated with the rainy season or water in general in the form of the Twisted Gourd symbol (ML006780; note the inclusion of the hallucinogenic San Pedro cactus in the context of the sacred mountain to extend the visual narrative; or, the simplest way, the inclusion of a symbol long known to materialize the misty place of the ancestors such as cloud forms, the chakana and checkerboard symbols, the Twisted Gourd, and the serpentine scroll.

The visual narrative of the Twisted Gourd symbol as an ideogram was as a timeless and therefore enduring Snake-Mountain/cave-Cloud/lightning “born of the gods” origin story of hereditary rulership. The task of Andean, Mayan, and Puebloan visual arts in the context of Twisted Gourd symbolism was to show the everywhere-present liminal “misty” state of the creator gods that was co-identified with “living water” and the timeless misty place of the ancestors as the vital biography of hereditary rulers in a hierarchically organized society. The mythology of the first organized religion of the first hierarchically organized civilizations of the Americas as encoded in Twisted Gourd symbolism begins and ends with the role of the cosmic Serpent as primordial mist (liminal space), whose omniscient spirit was embodied in the water cycle, the primary metaphor of which was the Milky Way-sky river of life. That one metaphor was the basis of all storm mythology in relation to divinity, the materialized signs of which were wind, lightning, thunder, clouds, and seasonal water cycles. Out of the mists of the Serpent the sun god materialized, which formed the basis of all light and heat, hence the igneous : aquatic paradigm as materialized by the cosmic Plumed Serpent and the supernatural lineages that extended from it that were embodied in the offices of a hierarchical social organization. It is also important to realize that in the omniscient, everywhere-present misty space of the cosmic Serpent, a space that it organized into sacred roads (directions) to serve the material world just as a developer would first lay out the grid of roads for a new community, the possibilities of the seeds of all life forms also resided. The checkerboard pattern was at once a symbol for the Milky Way-sky as the realm of the cosmic bicephalic Serpent and also the overarching concept of the place of dualism, wherein the liminal and material realms met in the Mountain/cave. In terms of an archetypal ordering principle the Mountain/cave had mirrored forms as houses in the Above, Middle, and Below, e.g., the axis mundi conceived as a vertically triadic centerpole linking three great houses along a “road.” Puebloan stories of the Hero/War Twins who guarded the “high places,” folklore that placed them at the four corners of the Chacoan sphere of influence as well as at the centerplace on top of Mt. Taylor, the daily birth of the sun god from a cave in the east, clouds, lightning, wind, rivers, and the provision of seeds all referred to the backstory of the ancestral Mountain/cave as the archetypal centerplace of origin and the birth of the sun, when time began. It’s a story that the Maya shared with the ancestral Puebloans.

It is through the origin stories of the Zuni/Keres and the Keres Puebloans with their many parallels with the Maya’s Popol vuh that we get a real ‘from-the-beginning’ saga of what the first American agriculturalists who organized around urban centerplaces thought about human origins and their place in the cosmos. Until one surveys Twisted Gourd symbolism beginning in Peru 2250 BCE to the iconography of the Plumed Serpent (South American amaru) among the ancestral Puebloans, it is easy to miss the singular import of phrases such as “sovereign Plumed Serpent” in the foundational corn myth preserved in the Maya’s Popol vuh (Tedlock, 1996) and the early iconography of the cosmic Serpent at Vichama in Peru 3,800 years ago as part of the Caral culture where Twisted Gourd symbolism appears to have developed first, which was reiterated as the Milky Way bicephalic serpent belt worn by the tutelary deity of the Moche (ML003149). Likewise, without that context, it is easy to miss the import of finding the checkerboard (Milky Way, sky, time, a place of mist) and quadripartite symbols (cosmic Plumed Serpent) as the earliest form of religious expression of a pan-Amerindian triadic worldview on decorated pottery with cacao residues among Anasazi ancestral Puebloans at Alkali Ridge in southeastern Utah during the 8th century (Washburn, et al., 2013).

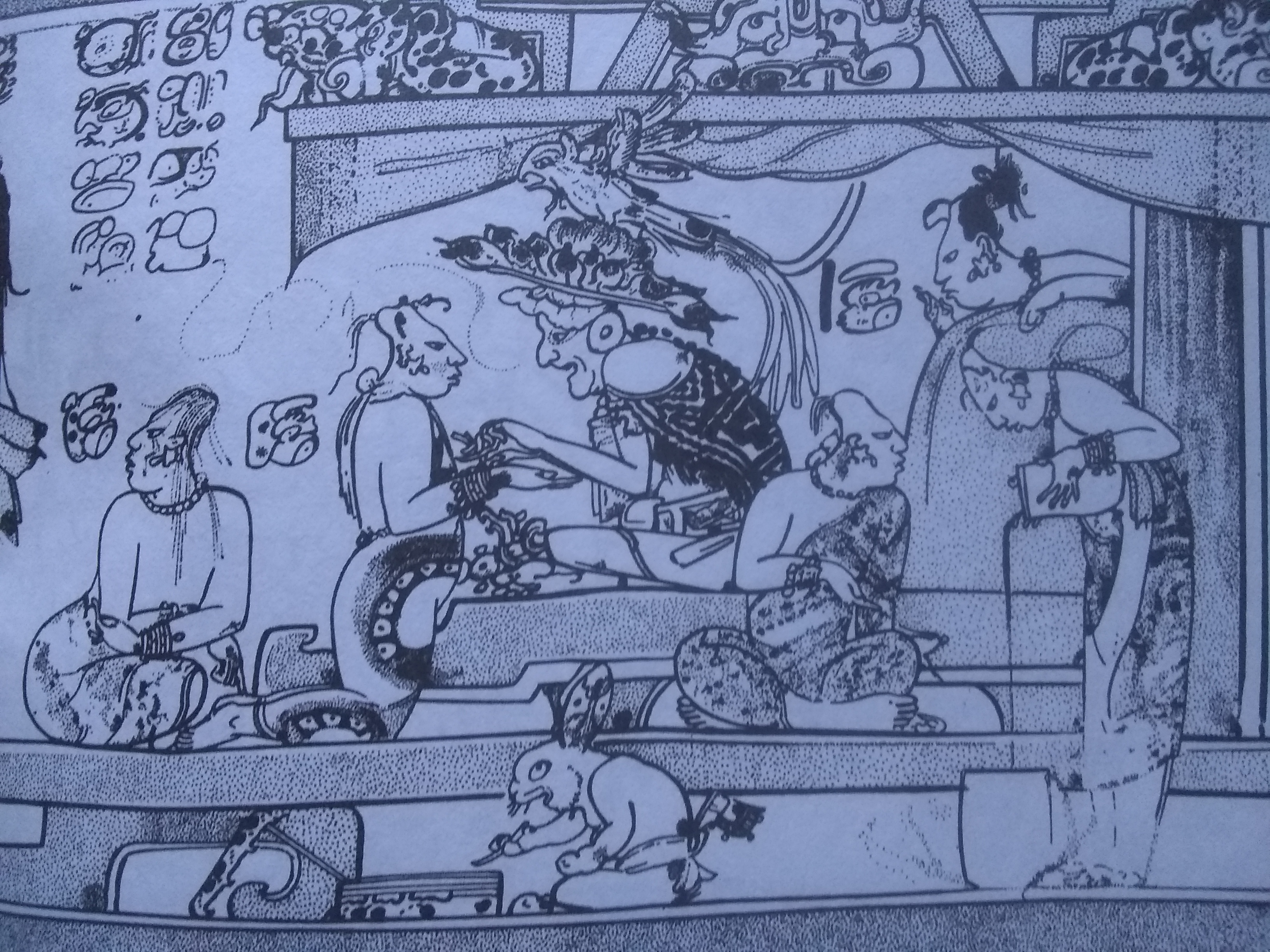

Checkerboard Context of Twisted Gourd Symbolism. The association between the Milky Way/cosmic Serpent as the checkerboard pattern and the Maya institution of divine kingship, which validated the social hierarchy surrounding the king through ancestor veneration of the revered dead of a dynastic lineage, is portrayed here on a mortuary panel from the Sak Tz’i’ polity by marking an ancestral mat of authority–the word from on high– with the Milky Way-sky checkerboard pattern which is being carried by the king’s sajal (image: Carter, 2014: fig. 4.11, the Josefowitz Stela. Drawing by and courtesy of Simon Martin). The elite rank of sajal was subordinate to the king and a position that administered subdivisions of a kingdom under the authority of the king.

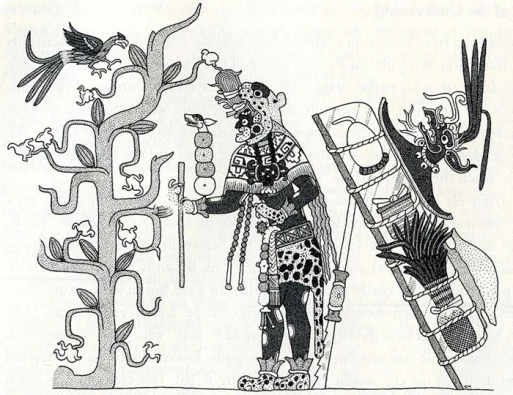

The Maize god (left) and Itzsamna (right) from the Dresden codex, pg. 9 (drawing by W.E. Gates, FAMSI). Itzamna, the first water wizard whose primary avatar was a bird, was the patron of divine kings and disappeared from the Maya pantheon when the institution of divine kingship largely came to an end in the 9th century CE. Itzamna is shown here wearing a cross-hatched (“black,” “misty” liminal state of the cosmic Serpent) cape bordered with the black-and-white-bar sideview of the Milky Way checkerboard pattern.

Over time and distance the interconnected Twisted Gourd symbols acquired a variety of shapes, but the particular form with the extended stepped fret that was seen at El Mirador (300 BCE-150 CE) and Nakum (550 -650 CE) was also characteristic of the Andean extended stepped fret that was prevalent in northern Peru in the Viru culture over whom the Moche retained control during the same period of time (200 BCE-600 CE; ML000065; ML000066; ML000234; the design was associated with the Milky Way, trophy heads from ritual warfare and social elites sitting on thrones (ML000608; note the conflation of the Cloud-Snake-Mountain/cave-Water concept and derivation of the S-shaped double-headed Serpent bar from the Twisted Gourd, which suggests that the Moche, like the Maya and ancestral Puebloans, had a concept of death as “enter the water” of the Milky Way river of life. See Osterholtz, 2018, for a historical review of the evidence for Anasazi violence).

Twisted Gourd symbol on early Classic Dos Arroyos Orange Polychrome, Nakum, Guatemala, Structure X pyramidal temple, burial 8, very likely a Nakum king or queen 550-650 CE in the context of archaeological evidence for a cult of ancestors and possibly a ceremonial site for the legitimization of power of the local elites (Zralka, et al., 2016:fig.15). PANC 044 was all but identical to PANC 047, in which 9 lithic artifacts were placed with shell and bone as an offering. Dos Arroyos Orange Polychrome was also in Tikal’s ceramic sequence, one of the two major Maya centers of political power (the other being the Snake kingdom) that displayed Twisted Gourd symbols. Note that, functionally, a stepped ceremonial platform that was so common throughout the pan-Amerindian sphere of Twisted Gourd symbolism could be inferred from this design, and that a ritual performance would at once also be occurring among revered ancestors in the underworld, which is what Puebloan ethnography revealed about Hopi beliefs and Moche art revealed about their beliefs (dance of the dead, ML012778; also see Ceremony).

Twisted Gourd symbolism on elite pottery at Izapa, Chiapas, Mexico, early Classic Dos Arroyos Orange Polychrome Mound 125, burial F-30 (Clark, Lee, Jr., 2016:fig. 8). These rare trade-ware vessels from the Maya lowlands pre-dated the Teotihuacan horizon at Izapa but were found in the same grave with Teotihuacan-style pottery, Kato phase 400-500 CE, that had been made on-site to imitate Teotihuacan’s prestigious ceramics. Aside from obsidian objects there was little evidence that pointed to any significant exchange of material culture with Teotihuacan. From South to North America, Twisted Gourd symbolism represented an elite family’s narrative of supernatural kinship and ideology of rulership, which suggests that sharing in Teotihuacan’s prestige meant sharing the same cosmovision and elite visual program (perhaps merging two elite bloodlines–Maya and Teotihuacan– as seen at Tikal, see Maya Connection), a pattern of ideological-not-material cultural exchange that was later seen between El Tajin (Vera Cruz Gulf coast) and Chichen Itza (Yucatan peninsula) after Teotihuacan’s fall from power c. 650 CE (Koontz, 2009). A piece of the local pottery (Kapoc Red-Brown or Tusta Rusty Red) was nested inside each of a pair of the imported Maya bowls (two ring-base, two tripod), which tends to support the idea that there was some type of symbolic or physical merger of two families. It may be that the merger was between a Maya female’s divine blood for religious authority and Teotihuacan blood for political authority (the overarching Kaloom’te military title of conqueror, a supreme warlord and overlord of divine kings). Twisted Gourd symbolism therefore spanned the pre-Classic to late-Classic period of development of social hierarchies in both Mayan and Mexican cultures, a visual program executed on elite ceramics, clothing, shields, and architecture associated with noble families that reached an apogee in the Toltec-Maya Quetzalcoatl cult of post-Classic Mexico that served social elites after the fall of the majority of Maya divine kings by 800-900 CE (see Maya Political Network and Mesoamerican Royal Marriages).

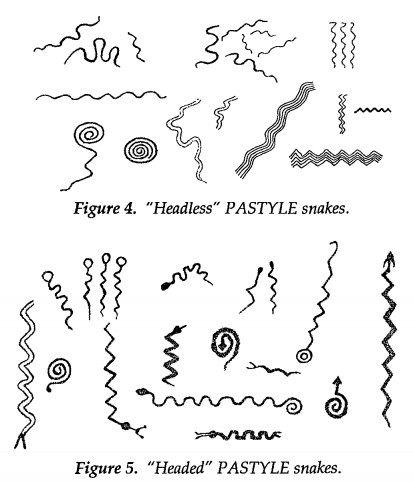

“Caves and water sources, so strongly connected to lightning and the rain deities in Mesoamerica, also have significance to lightning in the Andes, primarily as a metaphorical reference to emergence into a world or creation cycle or to accessing the tripartite cosmos, particularly through feline and reptilian animal familiars [KD: italics added to emphasize the essential role of the trinity of animal lords and directional Beast Gods as the fundamental aspect of supernatural ancestry of the hereditary dynasties]. Lightning is also commonly associated with meteorological phenomena such as life-giving rain, rainbows, and bodies of water, as well as destructive elements such as hail, fire, and resultant crop failure and destruction of the natural environment. Lightning and its various symbolic and anthropomorphic manifestations were of central importance to agriculturally based civilizations such as those under consideration herein, primarily because agriculture depends on rain and lightning is a harbinger of rain, but, perhaps more importantly, lightning’s power to create as well as to destroy, to aid a community or to damage it. …We found that lightning was associated with pre-Columbian rulership in both regions and, at least in recent times, with shamanism. Lightning bolts in both regions, as well as in several other parts of the world quite independently, are seen as a source of stone tools, including obsidian, flint, and other silica-based stones and transparent or translucent quartz crystals. In Mesoamerica lightning is commonly associated with riches and good fortune” (Staller, Stosser, 2013:11).